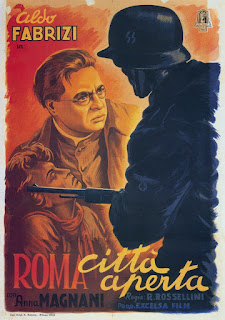

When In Rome Season: Rome, Open City (Dir Roberto Rossellini, 1h 48m, 1945)

Many cities are beloved of cinema; Paris, London, Tokyo, San Francisco, New York. Few, though, capture the imagination like the Eternal City; since the very birth of cinema, Rome has captured the imagination

of countless directors, and been the background for some of cinema's greatest moments. Over the next four weeks we will see Rome as the playground of the rich and the stalking ground of the paparazzi in La Dolce Vita (1960), as background to outlandish childhood nostalgia in Roma(1972) and as the diminished co-star of society drama, The Great Beauty (2013). Before all that, though, we must journey back to 1945, for arguably the most important film of the Italian Neorealist movement, Rome Open City.

Depicting a beleagued and divided Rome in early 1944 under Fascism, and largely focusing upon the fictitious events leading up to the death of Don Pietro (played by Italian

actor,Aldo Fabrizi, largely based upon the very real Italian priest, Giuseppe Morosini), Rome, Open City's very existence is miraculous, and its power as a piece of cinema undeniable,

cutting to the very heart of the Fascist movement, and the Italian experience under it, having lost none of its power, none of its realness in the decades after, and birthing an entire cinematic movement fully formed from

the heads of Rossellini and Fellini.

By 1945, Rome was in ruins; nearly six months after the Nazis had fled, the Allies soon arriving in their wake, little had been rebuilt, power was intermittent, and, at a point

where the Allies were still fighting in the North of the country, Roberto Rossellini was trying to make a film. His last attempt Desiderio, was left unfinished until Marcello Pagliero (also to be found starring in Rome, Open City as communist Resistance fighter, Luigi/Giorgio), finished it,

upon which Rossellini disowned it. Moreover, his career was already chequered, having made-albeit impressively verite-propaganda films for the Mussolini regime, and counted his son among his friends. Whilst the "Fascist

Trilogy" remain good examples of his early work, it also put him in contact with draft-dodging, and vehemently apolitical film maker, Federico Fellini, and the director who considered him his muse, Fabrizi. Together,

they agreed to make a film.

Rome's tautness and its verité style go hand in hand-we begin with the SS attempting to arrest Luigi/Giorgio,who alludes capture, thanks to

his landlady warning him, and Luigi/Giorgio is able to escape to the home of his friend, Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet), one of the film's many amateur actors that only add to the verité style of the film, his

performance naturalistic and genuine. Here he meets Francesco's girlfriend, Pina (Anna Magnani), and soon, Luigi/Giorgio is put in contact with the priest that, incidently is going to marry. Magnani dominates the first half of the film, a performance that strikes to the heart of the defiance and quiet strength of Rome's people-in no small part because she herself had mocked Mussolini and the Party-whilst you cannot take your eyes off her emotionally raw and staggeringly authentic performance. Small wonder she has become an iconic shorthand for the city itself.

Around

Luigi, Pina and Francesco, and the beautific figure of Don Pietro, however, the rot has set into the capital; not least because of the . Pina's sister, Laura (Carla Rovere), and Luigi's girlfriend, Marina (Maria Michi),

are working in a Nazi-owned nightclub, under the control of the sinister figure of Ingrid (Giovannia Galletti), who plies the latter with drugs, and, in order to afford the luxuries she craves, so Marina has turned to prostitution-in

sharp contrast to the worldly figure of Pina, these two women represent the degree to which Italian society, and Italian womanhood, has become corrupted by the occupying regime. With the film's true antagonist, Major Bergmann

(Harry Feist), suspecting that Luigi is at Francesco's apartment, he proceeds to raid the building, arresting its inhabitants in one of the film's great setpieces,

For, at its centre, Rome Open City is

a film about the loss of innocence in war, both of its two parts ending with the death of innocence in the form of of its only true innocent at the end of its first half, and the loss of faith, and what it represents, at the

end of the second. Seeing that Francesco has been arrested, we follow Pina as she breaks through the cordon of soldiers, only to be shot dead, in a stark moment that fully outlines the loss of grace, the death of the film's

one truly innocent person, and sets up the second half of the film, in which the film's other innocent, Don Pietro, becomes its central figure, shoulders the weight of having to find some redemption and grace among the

ruins, and carries on.

Whilst undeniably the film's protagonist, for the film's first half, so Don Pietro has largely been a bystander, trying to protect and maintain the community he acts as priest for,

including carrying out marriages as a patriot for the Italian people rather than allow the state's representative to do so. However, through his connection with Pina, a woman not only battling her own faith, as she is

heavily pregnant with Francesco's child but also, a general soul-searching, a loss of faith as she struggles to understand why God would allow Italy to suffer, which the figure of the priest must reconcile. It is in the

second half of the film that truly shows the quality in Fabrizi's performance, often having to come face to face with the banal evil of Bergmann and his men.

For, if Pina's narrative arc is an attempt to

reconcile faith and the ruins of Rome that she, and her fellow survivors must live in every day, imbued with the very difficult process of making a film in a city that is practically disintegrating around Rossellini and his

cast and crew, a film made on three kinds of scavenged film stock, often having to steal power or film guerilla-style in ruined buildings, it is with Don Pietro's stand against the Reich and for the resistance that the

film coalesces. The priest, in short, becomes a shorthand for the resistance, first assisting in the rescue of Francesco, and agreeing to hide them in a monastery, before being captured and

interrogated by the increasingly frantic Bergmann.

It is in the the figure of Don Pietro that the film's key message is carried; you cannot, will not be able to break the Italian people's spirit-here they

stand in a broken city, trying to carry on their lives under occupation, and no threat of violence or torture or death will stop them from protecting their fellow men and their way to freedom. Rome Open City may end in execution, may end in the death of innocents, but as the choirboys that reoccur throughout the film at the true innocents, the true future of a battered and beleagued Italy,

a destroyed and ransacked Rome, troop away from the aftermath, St Peter's Basilica rises, undefeated, colossal, and intact. Like the priest, Rome's body may be bullet-ridden and broken, but Rome's spirit stands.

Rating: Must See (Personal Recommendation)

Next week, Rome becomes the backdrop to one man's search for love, and happiness, as we arrive in the 1960s with one of

the greatest Italian films ever made, 1960's La Dolce Vita

Support the blog by subscribing to my Patreon from just £1/$1.00 (ish) a

month to get reviews up to a week in advance and commission your very

own review! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond. Further details on comissioning an entire season like this will be available soon.

Comments

Post a Comment