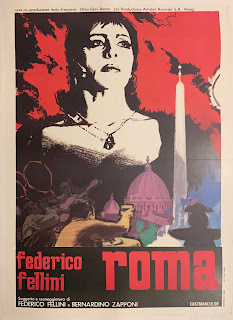

When In Rome Season: Roma (Dir Federico Fellini, 1h 58m, 1972)

Roma is a film about, and for, Rome. It is a film about Fellini’s reflections on the capital, on Rome in 1972, and a meditation upon the Rome of his youth in the 1920s

and 1930s, It is about a city steeped in thousands of years of history, about how the Eternal City is changing before his very eyes. It is a film about a young man trying to find himself in the Rome of his childhood, and trying

to recapture it in the tumultuous world of the 1970s. It is a film that melds fact and fiction, the spectacular and the mundane, the beautiful and profane, the sacred and the pornographic, as only Rome can, as only Fellini

can. It is a film where Rome is our hero and our protagonist.

Between La Dolce Vita and Roma, Fellini had stepped further and further from neorealism; whilst the stirrings of his more artistically driven, and psychologically

complex work of the latter 60s and early 70s can be seen in moments of La Dolche Vita, experimentation with LSD, and readings of Jung, spurred by a meeting with psychoanalyst, Ernst Bernhard would quite literally expand Fellini's

cinematic mind, and spur film making that borders on the experimental, the surreal, and the satirical. The twelve years between the two films focusing on the eternal Rome would not only take Fellini deeper into experimentalism,

but onto the international stage as a standard bearer for Italian cinema.

First, as Fellini battled being daubed as a "public sinner", would come 8 1/2 (1963), Fellini's arguable masterpiece, in which a director finds himself battling creative block and disappears into a surreal and highly autobiographical film-it would win Fellini two Academy

Awards, and net him a further three nominations, including Best Director. Today it is regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, a mirror held up to one of the medium's greatest directors, intensely autobiographical

and experimental at once. Fellini would celebrate his victory, in somewhat bizarre fashion, touring Disneyland with Walt himself the morning after the Oscars, a perfect example to the degree of the director's fame and

popularity, increasingly outside his native Italy.

A further meeting would see Fellini, via antiquarian Gustavo Rol, enter the world of spiritualism, that would colour his next two films, first making the beautiful,

but psychologically drenched Juliet of the Spirits (Giulietta degli spiriti, 1965), in which the mundane life of a housewife is turned upside down by her

female neighbour and into a world of dreams, visions and fantasies that slowly liberate her from her humdrum existence. Fellini would then follow this occultism into Spirits of the Dead (1968), a Poe-centric anthology film to which Fellini adds the vividly cinematic "Toby Dammit".Following this, Fellini would once again delve into dreams, with his version of the Satyricon (1969), in a film that is as absurd as it is beautiful. before turning documentary maker with Fellini: A Director's Notebook (1969) and The Clowns (1970), two films that blur the lines between documentary and pastiche.

Roma, at first, is a film of seemingly random incidents and sequences, with little joining tissue; compared to 8 1/2 and La Dolce Vita, there is no central figure, no Dante to travel through this Roman underworld with us. We begin with the younger and older Fellini-and

the film leaves us in no doubt that we are travelling with the director as a younger man. Even before we plunge into Rome's traffic in 1972, or Fellini's board and lodging in the 1930s, however, we get the closest

to a continual narrative that Roma manages, in childhood. Here, Fellini captures his own childhood in staggeringly evocative terms, from school, where his teacher symbolically leads his students

across the Rubicon, though the film will not reach it for another ten minutes, to the theatre, to the cinema, where, crowded onto seats and craning their necks to see, Federico Fellini falls in love with the medium

This

paean to his own youth complete, as we suddenly cut to a Roman coffee shop, so the film truly begins its two strands, that Fellini intercuts between seemingly on a whim, but in a way that builds, layer on layer, the personality

of his true protagonist. Thus, the film cuts nimbly back and forth over forty years; Fellini as a young man (Peter Gonzales) enters a labyrinthine bordello that will serve as his lodgings, meeting all manner of outlandish

and yet utterly human figures that he will soon share dwellings with, whilst the older Fellini, in the film's quasi-documentary of making a documentary in the present of 1972, crawls along in the presence of another company

of outlandish and bizarre figures-the motorists of Rome, as the camera truck rises above the chaos to film the film's true protagonist, to film Rome.

For, aside from the younger Fellini himself, who the film

later depicts falling for the charms of an older prostitute, and who cuts an undeniably handsome figure through the dilapidated glory of the city in the 1930s, even in the faded grandeur of the second brothel, all around Fellini

is grotesque and outlandish, and often perverse. The madam of the first brothel is a colossal figure, barely able to move from her bed, her son holding some unknown and quasi-Oedipal connection to her, whilst around the colossal

and labyrinthine dwelling, children and further women, and old, and dilapidated men lurk. The film's other brothel, that Fellini does not visit, is dehumanising, filled with the old, and the desperate, penned in as leering

men jostle. In one of the few scenes of the Rome of Fellini's youth that encounters the ancient, the city that once was, Ancient Rome is toothless, a mutilated statue mutely standing guard outside a school.

The

people of Rome of 1972 are equally lurid-Fellini was never an overtly political film maker, and his approach to the schism between generations, as students stage a sit in that the film returns

to several times, is to immediately juxtapose with the near riotous crowd of a variety show in the 1930s, as if to indicate that Rome's generations have always been fractured, always been disappointing to their forebears,

as draft dodgers and layabouts of the 1930s are compared to the very generation that they became lambasting the young of today. Rome has seen it all before, and Fellini's free-associative back and forth through memory

and the present adds layer after layer in a film that, at first, may seem a series of a random, and often seemingly unconnected spiderweb of events, but slowly build up a picture of a city at the heart of civilisation, rowdy

and wild, and staggeringly alive.

Two sequences, however, cut to the heart of what the director has to say about his subject-the first, Fellini at his most outlandish, considers Rome's other great inhabitant,

the Catholic Church, with a bizarre, at points unsettling, and ultimately comic fashion show held by the faded but still beautiful figure of the Princess (Pia De Doses) in which everything from roller-skating cardinals to

ominous cloaked figures to neon-clad priests stride the catwalk before a staggeringly bizarre appearance by the Pope himself, haloed in psychedelic swathes and towering over the massed clergy, brings this otherworldly, and most Fellini-esque sequence to an end. Whilst it ran foul of Italian censors,

in its uncut beauty in modern releases, it remains perhaps the high point of the film. a beautiful, strange and-quintessentially Fellini-dreamlike moment, exhuming a thousand-plus years of Rome's longest relationship and

pouring it into this sequence.

with his modern day film crew sees the film crew and digging the Rome Metro come across and marvel at the beauty of an untouched world below the modern city, only to become aghast as the air slowly destroys

this priceless marvel, the desperation of the female member of Fellini's film crew falling into resignation as treasures without count erode and weather away into nothingness. Rome's forward charge, its vitality, comes

at the cost of its past. Rome marches ever onward, perpetually in flux. As Gore Vidal, found seemingly in media res, declaims to camera, "What better place, than in this city which has died so many times and was resurrected

so many times". Fellini merely adds one more death, one more resurrection to the pile, in homage to the deathless, eternal Rome.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Next week, we bid farewell to Rome, with the city in the 21st Century, as backdrop to a modern critique of Italian decadence, in The Great Beauty.

Support the blog by subscribing to my Patreon from just £1/$1.00 (ish) a month to get reviews up to a week in advance and commission your very own review! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond.

Further details on commissioning an entire season like this will be available soon.

Comments

Post a Comment