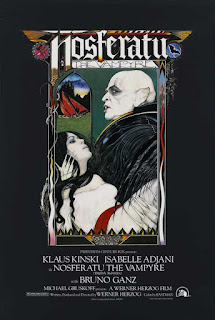

Best Fiends Season: Nosferatu The Vampyre (Dir. Werner Herzog, 1h47m, 1979)

It's easy to regard Herzog as purely an artist in the cinematic, a director who makes films for the pure pasison of it. To be fair to him, that's indeed what some of his films are, and the director's ouvre are better known, with a few outliers, for their critical, rather than commercial acclaim-indeed, few, even of his most famous films made box-office back at their time of release, whilst only his spellbinding documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2011) making its entire budget back whilst still in cinemas. This, though, is a bit of a misnomer, as though Herzog is somehow allergic to any creative venture not purely driven by love for the medium. Step forward, Werner Herzog as actor, narrator, and unexpected internet superstar (not bad for a a man who still doesn't carry a phone, despite his documentary of 2016, Lo and Behold, exploring the cutting edge of technology and its most burning questions.)

Thus begins-or rather, began-the phenonemon of Herzog as high-brow vox-pop cum unexpected voice actor in his autumn years seems to have kicked into life with 2005's Grizzly Man, in which Herzog explored the life and untimely death of Timothy Treadwell and the bear he studied for nearly fifteen years-the other career of Werner Herzog. Cameos in The Simpsons, American Dad, The Boondocks (in which he plays himself), and, somewhat inevitably, Rick and Morty, in which that curiously iconic Bavarian-English accent took centre stage. Live action appearances in series as far apart as Parks and Recreations, in which, laconically, he annouces he is moving to Orlando to be closer to Disneyworld, and The Mandalorian, in which he plays an Imperial agent, leading us to a bizarre reality where action figures of a 79-year-old auteur filmmaker jostle for space with the series' other, somehow less outlandish characters. Heck, he's even played opposite-and been offed-by Tom Cruise in one of the Jack Reacher films.

This is to say that Werner Herzog, whilst not on everyday terms with the cinematic mainstream, still has no problems paying it a visit every so often-and no better example in his filmography than Nosferatu The Vampyre, an adaption, reimagining, and homage to the 1922 original, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, a superbly rendered, remarkably paced, and yet undeniably Herzogian retelling of the tale in which Klaus Kinski's sublimely creepy version of the Count Dracula haunts the film, in a performance that is predatory as it is ultimately bathetic, as Bruno Ganz's Jonathan, and Isabelle Adjani's beautifully haunted Lucy Harker, attempt to stop the Vampyre, in a film that ranges between surprisingly straight horror, a curious danse macabre as the Count's machinations set plague loose among the people of the unfortunate town, and a curiously humanistic element to the doomed, and life-weary vampire.

In broad brushtrokes, Herzog recreates the backbone of Dracula-our hero, Jonathan, is sent by his employer, Renfield (an enjoyably deranged, manically giggling performance by French avant-garde, and co-director of Fantastic Planet, Roland Topor), to Translyvania. Here, he is warned that the castle of his would-be client, Dracula, is dangerous, that none have made it back, and that his prospective employer is likely supernatural. Here, thus, as the strains of Das Rheingold's opening movement, that ethereal sense of mystery pitted against churning current, comes the traverse, with Ganz's figure tiny against the elements, until, against the sky, comes the ruin of a great castle-not the proud jut of Bran Castle, used in the 1931 version, but a mere remnant, a broken thing among the fog. Harker is escorted in by the sparse servants, the door opens, and there, of course, stands Klaus Kinski, as Dracula.

Kinski's version of the Count stands alone for two major reasons. Firstly, alone among Kinski's work with Herzog, there is no sense of the usual anger, the magnified and directed rage that the other film the duo worked on together-indeed, there's more than a few stories of the production of this film seeing Kinski in an unusually calm state, withstanding hours in makeup. The performance he gives, thus filleted of rage, leaving Kinski's natural acting talent is unlike any other major version of Dracula in cinema up to this point. Compare him, for example, to Bela Lugosi's mannered aristocrat, full of at times hypnotic charm, and aloofness, keenly aware of how much power he holds over the mortals who stray into his lands, or Christopher Lee's toweringly masterful mix of booming camp and cool menace, as capable as biting throats as chewing scenery.

Kinski stands alone. Or at least, mostly alone-there's vestiges, as one would expect for a film that draws so much from the 1922 film, of the legendary Max Schreck's perforamnce, but Herzog draws far more from the figure-Schreck's Count Orlok may be the German Expressionist movement's greatest creation but aside from the striking appearance of the vampire, he is little more than a cypher, a frightening, magnificent but largely hollow performance. Kinski, in a word, makes the vampire pathetic-far from the beautifully horrifying creations of Lugosi or Lee, or the positively feral Orlok, Kinski's Dracula is-yes- tragic, a thing that was once a man trying to recall his humanity, wanting to die, but unable to do so. There is, in short, something of the Byronic to Kinski's figure-his attempts to find connection, even if it means drinking the victim dry, drives the character forward-a commonality in the post-modern vampire, but starkly unusual in the dying months of the 1970s.

He becomes besotted with Lucy from the moment he sees her picture in Jonathan's locket, his behaviour around, and visitation to Jonathan feel less the movements of a predator, more a pathetic, often lost figure that watches people sleep. That Kinski and Herzog give him, for lack of a better word, bite stops the film from being a maudlin character piece-for, once he is discovered to be a vampire, the film nimbly pivots, and it is here perhaps Herzog's biggest change. Dracula in his myriad forms has never exactly moved beyond his psychosexual-cum-fear of the Other hinterland-Kinski's scenes with Lucy may lean into these, into the predatory norm of the Vampyre, even if it becomes his undoing-but Herzog also casts Dracula as agent of social change.

For, once Dracula sets sail from Transylvania, arriving in the town of Wismar with the sudden, and, in a film that has more than its fair share of grand scale, impressive appearance of an entire ship, looming into shot, and coming to a haul, only to prove a harbinger of both the vampire, and via rats, (Herzog used over 10,000 rats for the film, causing one of his locations to balk at the furred multitudes), plague, with the entire social structure of the town slowly begins to crumble, as the plague runs rampant through the town, leading to a truly bizarre vignette where Lucy finds herself among a group of revelers, who have resigned themselves to their fate-Dracula is not merely attacking individuals, but society itself.

Against this, Herzog places the perfect foil-against the figure of Dracula clinging to life, Herzog presents Adjani, this incredibly lifelike figure, this wide-eyed young woman clinging to life, even as the plague decimates those around her-at once the innocent, often doeish figure of the archetypal prey of the vampire, and yet, despite the hardship, and her eventual death at the hands of the vampire, the one who eventually vanquishes him, in the film's biggest debt to the 1922 original, and the biggest diversion from the original Stoker work.She feels, in the ouvre of a director whose works so often focus upon men against impossible odds, against the very world itself, a lighter touch, a woman surmouting the odds not through a show of power, but through love.

Around her, though. Nosferatu the Vampyre is a gothic tinged showcase of Herzog at his best; from top to bottom, there is the sense of decay that so many directors never quite get when depicting the gothic-the film is steeped in it, drenched from top to bottom in the dark and macabre, from the opening sequence, filmed in the national museum of Mexico, portraying real embalmed bodies, from tiny children to hunched elderly, a parade of death and life. Between this and the otherworldly ending, in which a turned Jonathan, having been bitten by Dracula, rides off to repeat the process of the lonely, world-weary vampire, lies what may well be the most accessible film of its director's career, but in the hands of Werner Herzog, Nosferatu the Vampyre becomes a masterclass of the gothic, of the vampire writ large, of good and evil, as only this mastercraftsman of cinema can create.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment