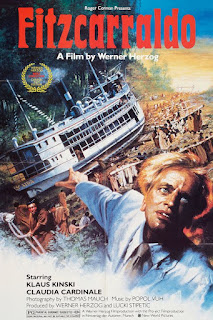

Best Fiends Season: Fitzcarraldo (Dir. Werner Herzog, 2h37m, 1982)

No director captures ambition like Herzog. A vast chunk of his documentary cinema are portraits of men (and occasionally women), pushing themselves to the brink of human ability. 2007's Encounters at the End of the World focuses upon the people working at the extremes of the South Pole, as this last great unknown undergoes irrecoverable change, whilst 1997's Little Dieter Needs to Fly, another documentary, recounts-and recreates-the experiences of a pilot imprisoned in Vietnam, and Land of Silence and Darkness is a masterful, and at many points, inspirational piece of cinema about Fini Straubinger, a blind and deaf woman that uses her condition

to help others with her experiences.

In Herzog's narrative cinema, meanwhile, his filmography is dominated by similar, if larger-than-life depictions of the almost-quixotic ambition of mountaineers (1991's

Scream of Stone) or Jewish strongmen pitted, in fable-like terms, against the Third Reich (2001's Invincible). Even the rare duds in Herzog's filmography, Rescue Dawn (2006) and Queen of the Desert (2015) remains fairly stirring depictions of ambition and human versatility, if otherwise flawed. This is nothing, of course, to compare to the ambition to the man behind the camera. Herzog, at points, is practically a mirror to his protagonists, a man driven

by his vision to moments that, at points, border on madness.

Some of these, of course, have long since passed into pseudo-mythology-the theft of the camera that he used up to Aguirre, the shoe cooked and eaten on camera after he lost a bet to Errol Morris (Morris's own oeuvre is as remarkable as the leathery delicacy),

the narrow escape from his (and his crew's) potential death, making La Soufriere (1977) on the imminently-erupting island of Guadeloupe, hypnotising his entire cast for Heart of Glass (1976), and being shot midway through an interview with the BBC's Mark Kermode (though this last one may have been staged for the camera, begging the question, "who else would get shot with an air rifle on camera for the pure cinema of it?").

And

then there is Fitzcarraldo, a film where the ambition behind the camera perfectly meets that in front of it, where Klaus Kinski (who else?) practically becomes Herzog's avatar,

a would-be rubber baron risking all-including his life-in traversing the perilous Amazon to claim unreachable land to make his fortune and bring opera to his home town of Iquitos. It is the perfect Werner Herzog portrait of ambition, a film that raises up the key themes of Herzog's work to the point that Kinski's Fitzgerald becomes almost godlike. It is a film that, in almost

breathless terms, explores the sense of epic adventure that plays around the edges of every Herzog film. It is a film where, both in front of, and the camera, Kinski and Herzog do the impossible, in one of cinema's most

madly spectacular moments, done for real in front of cameras in the middle of the Amazon rainforest.

We begin with Fitzgerald. In comparison to Kinksi's other figures, Fitzgerald is openly heroic-a far cry from

the sadistic Aguirre, the wildly crazed Woyzeck, and Cobra Verdi's manipulative da Silva and the broken figure of Dracula, Fitzgerald is an openly good person, a man ultimately driven not by the lust of power, or control, but by his love for opera, his passion, and knowledge of it palpable. His drive throughout the film is, after all, to build

an opera house for Iquitos, opera is practically his reason d'etre, and his guide through the jungle, with gramophone in hand, is so often accompanied by the voice of Caruso-it's a little noted fact of the film that

Caruso playing becomes a cinematic shorthand for fortune smiling upon Fitzgerald, from his storming into a party to demand his beloved opera be played on the battered record player, to serenading the encroaching native forces,

to perhaps its most famous appearance, as the film's iconic moment, the almost dream-like raising of the entire boat, plays out to the strains of La Boheme.

The film, after all, is buttressed with two opera performances, highlighting the transformation of ambition, and the journey that Fitzgerald/Fitzcarraldo goes on-he arrives to

the performance that opens the film rowing a boat that has broken down, grimy, and has to beg the attendant for entry. At the finale, perhaps one of Herzog's greatest sequences, he returns, triumphant, cigar in hand, sitting

atop the boat that has brought him tantalisingly close to success, an opera company spread around him, bringing, a man of his word, the opera back to Iquitos. It is a moment of pure, unadulterated, triumph-it is, without doubt,

the closest any of Herzog's major narrative films gets to a moment of victory over the impossible. It is made all the more remarkable by what lies between these two performances, these two great homages to opera.

What

lies between them is an adventure that Herzog's entire cinematography up to this point seems to have been leading to-in short, Fitzgerald seeks to construct an opera house in Iquitos (something his real life basis, Carlos

Fitzcarrald managed to do in 1897, though, astonishingly, the first performance ever held in the opera house is that which opens Fitzcarraldo itself). To do this, having already failed in building a railway across Peru-a location that the film briefly-and bizarrely visits, with the bereft and clearly declining station

master (a masterclass of a cameo from Brazilian actor Grande Otelo) a moment that feels as sudden as it is a portrait of a man clinging desperately to purpose. Fitzgerald-Fitzcarraldo as the natives have taken to calling him,

is thus a marked man-his debt apparently, his title as "Conquistador of the Useless" secured.

And yet, despite his bad luck, his poor fortunes, and Kinski's absolutely bastardish behaviour between

takes, typified by the single most infamous moment of 1999's My Best Fiend seeing Kinski scream his lungs out at an unfortunate member of the production team, something that left one of

the chief's of the native population offering to murder the bellowing maniac for Herzog, we cannot help but empathise with Fitzgerald. Herzog's films are so often packed with the clearly legend-set anti-heroes of his work, men and women stumbling on the doorstep to fame and glory, that to see Kinski

as-yes-underdog, is at points startling. In sharp relief to the maniacal motiveless malignity of Aguirre, we understand why Fitzgerald must build his opera house

Much of this has to do with the way that Fitzgerald as a character is built through the first act-the film gives him after all, a superb foil in the form of Molly

(Claudia Cardinale), his "in" to high society, as well as his financial backer and-though the film never confirms their relationship, the mistress to Fitzgerald. Perhaps this is where he differs most from Kinski's

other protagonists, given an even keel, and a surprisingly plausible plan to buoy him to his success. The plan itself is comparatively simple-sail up the Pachitea, and, in the few hundred metres between it and the otherwise

treacherous Ucayali, move the boat across and sail on to utterly virgin and unclaimed rubber trees. Fitzgerald raises the money, wastes no time in assembling a crew, buys a boat with Molly's money, and proceeds to set

out to make his fortune.

Here, Herzog is in his element-the early part of the cruise is, in essence a series of character studies, from the captain, Orinoco Paul, to the distrustful Cholo, the engineer of the boat,

to Huerequeque, the cook, whose entire appearance is a bizarre set of run-ins with the rest of the crew, before he inevitably abandons them. With the arrival of the natives, the film jumps a gear, not only in its remarkable

use of tension-at points, Herzog films only the hands of the watching natives, resting upon the balustrades of the ship-but also in the raising of the idea of these Europeans as somehow representative of godhood-though they

don't quite fool the natives, there's still a sense of respect-or perhaps the decades of enslavement leaving its mark, as they accompany the boat up-river.

What follows is perhaps one of the remarkable sequences

in the entire western cinematic canon. It's easy to riff off Fitzcarraldo, to boil it down to "Werner Herzog moves a 320 ton boat up a hillside, on screen, for real". It's even easier to critique why Herzog did it, why, in perhaps the most outrageous moment in western cinema since the silent era, he chose to do this almost insanely scale thing, and why this film, in a brief sense, has a death toll from

illness and accident. It is something unimaginable in today's risk-adverse cinema. Today's cinema would make this model-work, or CGI, the practical, the moment divorced from reality.

Absolutely, one cannot blame modern cinema for its focus upon safety over veracity when it comes to things of this scale. And yet.

And yet, Fitzcarraldo is nothing without this moment. It is spectacular. It is jaw-dropping. There is something absolutely elemental about it all-it brings tears to the eyes that this is happening (even if, as the revelatory

documentary, Burden of Dreams, released in the same year and directed by Herzog's friend, Les Blank, reveals at least part of the work is a 20-ton bulldozer pulling the boat upward). It

is madness and beauty and cinema at its most impossible. The boat rises. The boat rises. This should be impossible, to make a film in hostile jungle, with a half-mad co-star taking verbal chunks out of everyone, with your

first star, Jason Robards, invalided from the film, suffering from dysentery. This film should never have been made, and certainly should never have been so triumphant, so utterly sure of itself.

And yet, despite everything, despite Kinski's screaming fits, despite the jungle, despite the 320 ton boat, despite the hillside and the mud, and the chaos, the boat rises. From a gramophone, plays Caruso, into the humid air. Kinski stands in the foreground, the boat impossibly perched halfway

up an Amazonian hillside. He turns, Herzog watching through the viewfinder. Together, they watch the steamer slide ten, maybe fifteen feet up the hillside. Of the five films the two men made together, all five may be regarded

as seminal cinema, or leading examples of New German Cinema. All five of them are, undoubtedly among the greatest films ever made. But only Fitzcarraldo, towering above the landscape, prow pointing into the Amazonian sky, feels like the sum of all Herzog's themes, of his bold-or foolhardy men battling against the odds. Only Fitzcarraldo feels like the summit of Herzog and Kinski's working relationship. And still, the boat rises. Forever.

Rating: Must See (Personal Recommendation)

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment