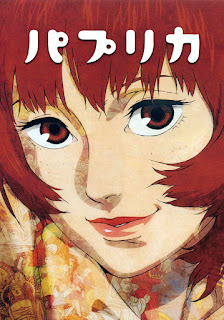

Ani-May: Paprika (Dir Satoshi Kon, 1h 30m, 2006)

Perhaps no loss in animation is as great as that of Satoshi Kon. When Kon died in 2010 at the age of just 45 of pancreatic cancer, he left behind perhaps the greatest, the most untouchable, and nigh-flawless filmography of any anime director, period. In just four films, and the seminal anime series, Paranoia Agent, Kon explored the human condition, from the disquieting Perfect Blue, a meditation upon idol culture, to the ode to cinema and memory that is Millennium Actress, to the greatest Christmas movie of all time, Tokyo Godfathers, to the subject of today's review, the mind-bending Paprika, in four films that masterfully, in Kon's ineliminable style, explored the blurring of reality and fantasy against a backdrop of modern Japan. In doing so, Kon not only influenced the entire medium of animation, but cinema in general, with his trademark approach, his visual style echoed in films like Black Swan and Inception.

Paprika, thus, is an exploration of the mind, in which a dream therapist, under the guise of the titular Paprika, explores dreams, only to find herself increasingly caught up in the theft of the machine that allows her to enter these dreams, and the plots of her superiors, in a work that masterfully blurs and converges the dreaming and waking worlds in an utterly riveting and visually stunning tour-de-force of animation. It is, in short terms, the capstone, the apex of Kon's career, and a bittersweet reminder of what Kon could have gone on to do, as well as an undeniable (and perhaps overglossed) influence on Inception. It stands as Kon's legacy, his epitaph, a reminder of just how much this single director changed the respectability of anime as a medium, and captured the dark and disquieting heart of his native country beneath its cutesified skin.

By 2006, Kon had been planning Paprika for several years; certainly it shares far more in common with his first two films than Tokyo Godfathers; indeed, it's often been suggested that Paprika could have been his second, rather than his fourth and final film. Nevertheless, its place at the apex, at the peak of Kon's ability as a director, is unquestionable. Following the character of Paprika, a therapist who appears in peoples' dreams to help them through often traumatic events, and her real-world counterpart Atsuko Chiba (Megumi Hayashibara/Cindy Robinson), we are led into the theft of the nigh-miraculous DC Mini that allows dreams to be entered. What follows is a slowly unfurling conspiracy that sees Atsuko and Paprika, together with the DC Mini's creator, Tokita (Tōru Furuya/Yuri Lowenthal), and a detective that she is treating, Konakawa (Akio Ōtsuka/Paul St Peter), as they traverse through the increasingly overlapping worlds of dreams and reality to save both.

Thus, we are treated to lush visuals as Atsuko/Paprika, Tokita and Konakawa enter dreams in search of the thief or thieves behind an ever-growing dream that ensnares people, including the hapless Tokita

in the second half of the film. We see Konakawa confront his demons, in a recurring looping moment that masterfully plays with the rules of cinema-indeed, as I'll come on to discuss later, this is as much a film about

those dreams put to celluloid that we call film, as the dreams of our sleeping hours, we see Paprika and Atsuko discuss their inter-relation.

As the dream overtake the minds of those dreaming, so bizarre moments

of violence and babbling dialogue become commonplace, before, following a disturbing confrontation with the figure behind the dream, whose own motives are, whilst extreme, an acceptable reaction to this technological intrusion

into the "one refuge humans have from the modern world", as they put it, before the parade, long teased through the film as a manifestation of the dream, bursts into the real world. What follows is nothing short

of a battle for the dreaming world and the real, that pushes Kon's visual ambition to ever greater heights in a burst of glory.

What lends the film its particular quality-the international tagline boasted the

immortal line "this is your brain on anime" is Kon's fluidity, his incredible ability to use animation in a way that no other medium could possibly give you, to play with the rules of space, to blur, as he did in Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress, scenes together. Nowhere is this better seen than in the film's opening credits, and in its final battle, two moments where we see Paprika move across the city through frames,

stepping in and out of adverts, blending in and out of the people around her, and in the final parade sequence, we are treated to some of the most astonishing visuals ever put to cel, a blurring rolling blend of the real, the imagined, and everything inbetween.

But Paprika is more than just clever visuals; the way in which the film masterfully blends the real and the dream is done in incredibly cinematically aware ways-he deliberately breaks several rules of

film making, loops sequences over and over, including the corridor sequence in which Konakawa chases a mysterious figure, sees a shot figure fall repeatedly, each loop of the moment giving him more information, a greater insight

into what it represents, and eventually coming to terms with its meaning, its relationship to a childhood friend, and its return, late in the film's finale, is a masterful bit of storytelling as he finally gets his man.

Not only this, but the animation carries much of the weight of the narrative, Kon often showing, rather than verbally telling a major moment or plot-twist in this high-speed narrative.

At the centre of this film

is its characters, and through them we see these glimpses of the waking and dreaming worlds; Paprika herself is a fluid figure, and one could even argue that she is a meditation on the avatars of the virtual world, a far more

playful, colourful individual than Atsuko, even as Atsuko herself eventually comes to term with the fact that they are one in the same. Tokita, for his part, is a charming and sweet figure-another director may have taken a

morbidly obese character either as a creep or a pathetic figure, but it is arguably he that goes through the most, searching for his friend even as the dreams claim him. Konakawa, for his part, feels at once a man searching

for a purpose in his dreams as they flit between genres in the opening sequence, and afraid of dreaming, at least in terms of cinema, his childhood eventually providing the key to this

The dream itself, though,

is perhaps the film's main character, growing from a single sinister doll that represents the film's antagonist, slowly entrapping scores of people, including several from Atsuko and Tokita's department, who crash

and babble nonsense, the translation keeping the nonsensical sense of the waking dreamers in moments that are as amusing as they are alarming, through scenes. By the time it arrives in the waking world, it is a colossal, all

encompassing parade, the score by Susumu Hirasawa lending it, via the early usage of now iconic voice synthesiser brand Vocaloid, an unearthly almost-human sense that only makes the parade more uncanny, as it marches on through

the streets of Tokyo, an uncomfortable manifestation of materialism, of Japanese politics, of the seedy underbelly of Japan as a country.

Kon's films, certainly, never step away from sensitive subject matter,

never stoop to stereotypes-this, after all, is a director who brought empathy to a homeless man, a transwoman and a teenage runaway and made them latter-day Magi, and Paprika is no exception. To say that Kon has the grey and grey morality of his peer, Hayao Miyazaki, though, is a complete lie-Kon's films often dwell on cruel men, from the violent stalker of

Perfect Blue to this film's antagonist, a representation of both the overly tradition and the technophobic turning a piece of technology to a weaponised rise to power. Whilst Paprika may be a film about dreams, there's nevertheless a sense of that Jungian approach to the collective unconscious, as though the thoughts of the dreamers leach politics, sex drive, and uncomfortable

and often bizarre imagery into the dream parade and eventually into the real world.

But, more than any of his films than perhaps his ultimate anthem to cinema, Millennium Actress, Paprika is a film about cinema. Several key sequences take place in movie theatres, and we see later that the

individual dreams of the dreamers appear on cinema screens, a moment you cannot help but wonder if Pixar lifted for Inside Out. We see this through the eyes of Konakawa, whose childhood fascination with cinema is eventually revealed, and his breakup with cinema laid bare; his sequences in particular are astonishingly

cinematically literate, Kon's love of the medium clear; Paprika ends on a moment of utter catharsis, as Konakawa falls back in love with cinema, and journeys into the theatre once more.

Moreover, as with Actress, Kon's blending of cinema and dreams-perhaps to them they were the same thing-comes to the fore in several moments, as the rules of cinema break down,

or suddenly reassert themselves in the middle of a scene. As only the best directors-Lynch, Tarkovsky, Cocteau-can, the blending of dreams, of the idea of cinema as a dream, or, as we could more put it, a sense of a film being

dreamlike, Oneiric, is absolutely integral to Kon's cinema, and no film in his canon puts this point better than Paprika

Of course, we cannot talk about Paprika, cannot talk about dreams in cinema, and certainly cannot discuss the outstanding debt that cinema still owes Satoshi Kon without

addressing the Nolan in the room. I've seen Inception, years before Paprika, and like Darren Aronofsky's wholesale theft-and it is theft of the lowest,

slimiest order, especially for a director that eulogised Kon after his death, Nolan's Inception is a surface-level magpie-ing of Paprika by cinema's biggest magpie. Whole sections, from the iconic corridor shot to the dress sense of Elliot Page's

character, are less homage and more a theft of elements Nolan either bends to his narrative, or dumps in like the proverbial kitchen sink, stripping them of their context and reducing Kon's animation, as with so many live-action

adaptions, to merely a cool visual for the popcorn munching masses.

Inception, thus, is Paprika in all but name, a film for those who still cannot leap over the miniscule-high

fence of animation being an adult-appropriate medium, let alone Bong's inch-high subtitles. That Inception released barely a month before Kon finally succumbed to cancer feels, for what

little merit the film has, nothing more than an insulting coincidence, that its biggest influence slipped away unnoticed by the American cinema-going public dwarfed by the fact that Nolan still refuses to admit the influence

that Paprika had on his film.

Perhaps what you take away from Paprika most is this. Kon wasn't finished. Like any great creative with a life cut short, it is the films he didn't

make. At time of writing, his final film, Dreaming Machine, a robotic road movie, lies somewhere in a Japanese warehouse, 600 of a total of 1500 shots completed, fully scripted, fully storyboarded

and presumably fully recorded dialogue wise, . It, undoubtedly, is Kon's epitaph, his final burst of glory, and remains tantalising, with footage to be shown for the first time in French documentary Satoshi Kon: la machine à rêves. Whether it will ever be completed, either by another esteemed anime director, or even a western film maker, is perhaps one of the biggest questions surrounding

Kon's legacy. Like Richard Williams' astonishing life-work, The Thief and the Cobbler, its mythic status perhaps lends it something a finished film would never do.

But more

than this, Kon is just one of many great animators whose lives have been cut short by the brutal working conditions that continue to exist even in the highest circles of Japanese animation, and indeed in Japanese working culture

full-stop. Whilst Kon's pancreatic cancer may not have been immediately linked to overwork-though many commentators in the western anime community have noted his heavy smoking may have been a factor, there are other animators

still. From veteran Kazunori Mizuno, responsible for much of the bulk of the famous series, Naruto, to Studio Ghibli's own Yoshifumi Kondo, whose sole directorial debut, Whisper of the Heart, so many of these losses are only sharpened by the myriad tantalising glimpses at what could have been. Paprika is this final glimpse into the mind of a titan of animation, and it, like the dreams Kon loved to portray on screen, is all too fleeting.

We have the films that he did make though, these dreams on celluloid, these astonishing blurs of modern Japan and the otherworldly nature of dreams, or altered states, or memory together, held together with Kon's utter

control of the animated image, memorable characters, and often unflinching glimpses into the human psyche. Paprika ends with a moment in which, as the camera pulls along a series of posters

to settle on Konakawa, we see posters for Kon's previous three films, before Konakawa steps into the cinema for the first time in years. At the time, it's a knowing wink to the audience. In hindsight, it's a epitaph,

a reminder that, at his very best, Kon was a master of cinema taken far too soon. Paprika is a dream, fleeting, beautiful, but gone, like its director, all too soon, and what we are left with

is images, fragments of other worlds, that linger on into the dawn.

Rating: Must See (Personal Recommendation)

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment