Blockbuster Month: Jaws (Dir Steven Spielberg, 2h 4m, 1975)

It's the summer of 1974 and Steven Spielberg has a problem. He's a couple of months into a shoot for an adaption of a pulpy airport novel, a film already plagued by studio interference,

a writer's strike, and extensive re-writes of the film's script, not to mention the difficulties of shooting much of a film set at sea on location off the coast of California. Now his titular villain is having performance

issues, regularly either refusing to appear at all, or suffering breakdowns, or suffering, along with the rest of the cast, from the effects of acting at sea.

Fortunately for Spielberg, this malfunctioning actor

is an animatronic shark, jokingly named Bruce after the director's lawyer, its intermittent functionality rescquires Spielberg and screenwriter Carl Gottlieb to essentially work around their non-appearing Great White to turn

the film into a taut claustrophobic Hitchcock-at-sea battle of wits between the shark and his three human heroes, and Jaws goes on to be the highest grossing film of all time for two years, until a little space movie by Spielberg's friend George Lucas takes that particular crown (more on that next week).

But

more than anything else, Jaws is almost single handedly responsible, tidal wave of merchandise, and round-the-block queues for admittance et al, for kickstarting the entire "Blockbuster" concept into existence, a move that

steadily, between 1975 and 1993, makes a film just the centre of bespoke marketing strategies, and sees the slow transformation of the summer in cinema into a proving ground of colossal franchises after colossal box office

records, armed with colossal merchandise and marking lines, that stretches to this very day. This, thus, is the story over four weeks of how a shark, a farm-boy, a bat, and an island full of dinosaurs changed the face of multiplex

cinema forever, and how they laid the foundations to some of the highest grossing and most beloved cinematic franchises of all time.

Jaws begins, of course, with the shark. Or, perhaps, more accurately, the idea of the shark, a point of view shot as the shark swims through the ocean, accompanied

by Williams' music, the muscular two-note thump perfectly encapsulating the shark as a lief-motif. Following a duo of students heading from a beachside campfire, the shark promptly takes one of them in a brutally efficient

scene, and we cut to Martin Brody, (Roy Schneider), the relatively new police chief of Amity Island. After the discovery of the unfortunate victim of the shark, Brody begins to put pressure on the town's mayor, who stands

firm on the beaches remaining open, finally caving after the death of a local boy. A bounty is promptly placed on the shark, with local fisherman, Quint (Robert Shaw) offering to hunt it down for $10,000, whilst oceanographer

Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) arrives on the island and confirms that the first victim has not only been killed by a shark, but an abnormally large one.

When a tiger shark is promptly caught by the local fisherman,

the duo of Hooper and Brody have their doubts, with the autopsy of the shark producing no bodies. Hunting for the shark, the duo come across the boat, and body, of local fisherman Ben Gardner, both having been partly eaten

by the shark. This, though, is not enough to convince the mayor to close the beach, and on the Fourth July weekend, despite large amounts of security and patrols off the shore, the shark once again swims inshore, this time

into the local boating lake, and once again claims a victim, this time in front of Brody's eldest son, traumatising the boy. The mayor reluctantly agrees to pay Quint, and the trio set sail to hunt down the shark.

The

trio set out in search of the shark, and what follows is a series of altercations between the shark and the Orca, the trio hunting down the shark, first catching up to and briefly hooking

the shark on the line, before, in perhaps the film's most iconic shot, the shark rears out of the water behind the boat, and for the first time we see the size and threat the shark poses to the trio, before the shark is

tagged with a barrel. The trio retire to exchange wound and war stories, before the shark once again attacks, badly damaging The Orca, and, with Quint destroying the radio in a moment, of madness, the final fourth of the film is a battle of wits between the trio and the shark, culminating in the death of Quint, the loss

of the Orca, and the shark finally exploding, as the surviving Hooper and Brody swim back to shore. Roll credits.

It is around these three disparate figures that Jaws is at its best. Brody, essentially our protagonist, is the second (Duel's David Mann's being the first) of a grand cavalcade of everymen, of straight

off the street characters, characters that we can easily imagine ourselves being, that have become the hallmark of much of Spielberg's filmography, and many of his heroes. Brody, for his part, is a caring father, the film's

arguable moral centre, despite his relatively new status as the town's chief of police, as he attempts to get the beaches closed to protect the town against the threat offshore, and despite his fear of the water, a phobia

that is only hinted at, and never developed as the trio set off to hunt the shark, and eventually, despite the extraordinary situation he is put into, defeats and kills the shark. He is. undeniably, this film's hero, despite

the corrupt local government, his very adult fears, and his attempts to keep the peace.

If Brody is the everyman, the avatar for its audience, then Hopper is unquestionably the rationalist, and, unquestionably perhaps

the closest Spielberg has ever come to a character based on himself, a somewhat sheltered young man from suburbia who is thrown into the middle of a chaotic for a hunt of the shark, butting up against the much older Quint

as the two experts squabble, pick fights with each other and compare their expertise against each other. Yet, Hooper is also a charming, intelligent foil, particularly in the early half of the film to Brody, standing up against

the mayor of Amity Island, proving beyond doubt that the first victim was killed by the shark, and finally arming the trio with the eventual destruction of the shark. Moreover, as with Brody, he starts the tradition of Spielberg's

concept of the everyman paired with the intellect, a tradition that runs through the best of his filmography, from Close Encounters to Jurassic Park.

And then there is Quint. He appears suddenly in the school room, where the grieving mother of the shark's second

victim, Alex Kintner, with a grating of nails on a blackboard, a disturbance at this sobering event, a verité, grizzled ad-libbed maelstrom of a performance that practically storms into the film and sets up court as

Ahab to Jaws' Dick. In Spielberg's entire filmography, there are perhaps a handful of performances that match up to Quint in their pure electricity, a titan of acting essentially allowed free reign inside the film,

and none of them are as driven, as fleshy, as at once alarming and exhilarating as Quint. The shark needs Quint to act as adversary, and the film needs this battle between man and shark, Moby Dick transferred to 1970s Californian suburbia, and we see Shaw, despite everything, despite his alcoholism and his rivalry with Dreyfuss, drive this film forward, a colossal figure crashing through

the surf, harpoon aloft, to meet the shark that lurks at the centre of the film.

But it is when this mismatched trio are on the claustrophobic Orca, practically the fourth protagonist in the film, that Jaws is at its best. It is this lack of space, as the trio rub against each other, that the film truly shines, where they are forced to get

to know each other. What follows, in essence, is two generations of men; the generation who fought, as Quint regales in perhaps the film's most iconic lines of dialogue as he recounts the fate of the USS Indianapolis and

its shark attack, in the Second World War, and the post-war generation, represented by the young upstart of Hopper, and three types of men, forced to interact, to rub along, until, with the sudden explosion of violence from

Quint as his quest for revenge overtakes him, so this carefully built alliance between the fisherman, the police chief and the oceanographer collapses, and with it comes the loss of Quint.

Much has been made of

Jaws as allegory, from the blindingly obvious-masculinity in crisis post WWII-Brody's relationship with his children is the first in a veritable cavalcade of distant or absent or ineffectual

father figures, as he tries to connect to them through a number of scenes (one of the few things the first sequel expands on well) to the aftermath of Watergate and the distrust of local government. The Mayor of Amity, Larry

Vaughn (Murray Hamilton), has long become a shorthand for corrupt and feckless government, his reappearance as cultural touchstone during the 2020-2021 COVID pandemic, including a frankly eyebrow raising moment in which the

British Prime Minister compared himself to Vaughn (not for the first time), only highlights how much the film's critique of government remains just as biting as the shark itself.

Further out, with the population

of Amity itself, and one cannot help but consider Jaws being a melting pot of 1970s fears; the shark's first two victims, for example, are a young woman and a boy, and this fear of a ravenous

outsider preying on the youth brings everything from foreigners; whilst the insular and "Us and Them" sensibility of Amity, battling against the foreigner shark, the unwelcome infiltrator, is merrily subverted in

Spielberg's next two blockbusters where the alien and the outsider is championed by his everymen. Against this, and focusing far more on the opening stretch of the film, there's the sense of the shadow of an indiscriminate

death and, at least in the case of the shark's first victim, of an uncomfortable sense of sexual predation and death haunting the beaches of Martha's Vineyard.

Yet, the most barbed metaphor that Jaws has in store is a full-sale stab against the very idea of capitalism itself, of the little town staying open at any cost, even as the bodies pile up, the mayor and his Saturday-Morning cartoon

expansionism and willingness to feed this mobile maritime meat-grinder as long as the punters keep rolling in, only the brutal dismemberment of a bystander in front of Brody's son, a moment of harrowing misdirection and

cinematic economy, finally acting as leverage to Vaughn eventually bowing to social and economic pressures and sending the trio out to hunt the shark. Hell, there's even the impressively under-noted co-opting of Henrik

Ibsen's An Enemy of the People, a play ripping back the covers of 19th Century Norway to reveal greedy and immoral people, that acts as practical template, the incorruptible Martin Brody acting as stand-in for Ibsen's Stockman, a lone figure speaking sense to a financially blinded mob.

And it is here, in the stretch of film between the death of Alex and the death of Quint, the two deaths that bookend that great winding up of tension from first to last appearance, that

the genius, and it is genius, of Jaws arrives. Jaws itself is on screen for a staggering four minutes, a ruthless brevity that informed Ridley Scott's Alien four years later (a film that practically marketed itself to prospective studios as Jaws in Space), but where Alien's less-is-more is an entirely intentional act, Bruce's non-appearance is an altogether less intentional, at first, act. Let's

address the shark in the room-when the puppet, all 25 feet of it is on screen, properly on screen, it's, in a word, unconvincing. For vast chunks of the film, it barely worked, sank repeatedly,

its operation was further stymied by the fact that the latex surrounding the beast filled with water, and the machinery inside became repeatedly encrusted with sea-salt, blowing the film massively over its shooting schedule

and over-budget. Apocrypha even has a vengeful Spielberg trashing the huge animatronic wreck with his crew, much as the rest of the film's ships ended up rotting on a Universal Studios attraction.

But here's

the thing. Spielberg can't show us the shark, because the shark doesn't work. What he can do, via POV shots of legs trailing through the water from below, or via the infamous fin as it slices through the water, inevitably

accompanied by Williams' durm-und-strung co-opting of Stravinsky, is the idea of the shark. And through clever editing, through the nigh perfect marriage of music and imaging, through

Spielberg essentially rebuilding the film to fit in the lack of shark, Jaws is transformed from special effects draped over a plot of killer shark, to a thing of pure, palpable fear. Though

we see Jaws for four minutes, its presence is felt from the opening credits, where we are Jaws, moving purposefully through the ocean, to its explosive demise. Whenever we even see the ocean, there is the potential of the shark, and this, if nothing

else, is the momentum upon which Jaws runs, the threat of the shark, rather than its physical presence.

What gives Jaws this power, though, is two notes, low down on the musical

register. Du. Dum. Or, more accurately, "E and F" or "F and F sharp", depending on who you ask. It's a halfway house between the suspenseful scores of Hitchcock collaborator, Bernard Herrmann, evoking

variously human breath, the movement back and forth of the shark, and the work of Stravinsky and Debussy. It's muscular, it's efficient, it is the shark, it is the bones around which the rest of the main theme and the score as a general takes shape, as the film itself takes shape. It cuts off suddenly after the shark's attacks, it

rears into being when that fin cruises across shot, it's even used to trick and misdirect the audience at times, as the shark suddenly, as in its first appearance, rolls out of the ocean without the cue. It is the film

itself in miniature, and its perfect balancing, its suggestion of fear and menace, in Spielberg's own estimation, saved the film, and added $100 million to its colossal box office. But

more than anything else, it cemented the bond between Spielberg and Lucas that continues to this day, with a

And by Jaws being so camera shy, by being so illusory, when the shark finally appears, it is a moment of utter terror. It is the payoff, the "bang" of a fuse

that's been smoking for an hour and twenty minutes. By this point in the film, Jaws has killed four people, terrorised the town and already posed a threat to the Orca, and the tension is racked up to breaking point. The film appears to go into a lull, as the relaxed moments, these moments of efficient character interactions between the appearances of the shark,

take over from the rising tension. Brody, at the back of the boat, is chummung the water, to attract the shark. Cutaway to Quint, preparing the reels. Cut back to Brody, the frame now providing perfect tension, Schneider to

the left, a huge gap of negative space, of open sea behind him. We are waiting with bated breath for something, anything to fill this gap.

And in one of the greatest introductions in cinematic history, Jaws finally

enters the frame, not as a fin, but as a colossus, a mass of grey flesh and black empty doll's eyes. A beat, as Schneider straightens up, turns. String stab from Williams. Brady turns, and the shark is moving, gone.

Jaws is on screen for barely a second, and the stakes have already changed, the size of their as he stares at the space where the film's adversary was, takes a few steps back, the camera cuts to inside the Orca's cabin

as he steps back into it, turns, and delivers the immortal line. And here, Williams returns to the main theme, as the shark bears down on the boat, the colossal shape moves past camera, and our heroes begin to realise what

they're truly up again.

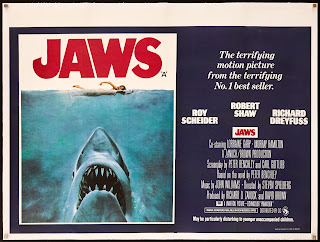

What they were up against, in short, was a monster. Let's start with that iconic poster, that encapsulation of everything Jaws is, the shark rearing from the depths in far more detail that we ever

see him in the film; it's now practically a shorthand, an image we barely even need accompanying text for, as Jaws makes way for everything from video gaming characters to cats, to IKEA's memetic soft-toy shark, not

to mention the ripoffs and homages that abound in film posters like Tremors (1990), The Meg (2018) and beyond. It's astonishingly simple, and utterly indelible. Yet, this was merely the tip of the shark fin of television and radio trailers, tie-in versions of the novel, press

appearances, and an entire ocean of merchandise, from t-shirts to toys, to a veritable smorgasbord of beach towels, buckets, spades, water pistols and other beach related equipment that practically codified the way that films

of this size market themselves. Jaws, if nothing else, is the blueprint for how the blockbuster does business.

Jaws changes cinema. In a parallel dimension, the shark works, and Jaws is the thing of wet Saturday afternoons, a wobbly rubber beast straight out of the b-movies,

not a Hitchcockian beast of half-glimpses and suggestions, Jaws is shorn of its suspense and power and the blockbuster arrival never happens, or at the very least has to wait a few years before

really finding its feet. With it, the high concept blockbuster arrives, the auteurist work of the early 1970s takes a back seat, and theatregoers everywhere begin to swap the (no doubt shark-terrorised) beaches for the multiplex.

For all its watering down by its largely terrible sequels, including, in all bluntness, two of the worst films ever made (the faddish Jaws 3-D and Jaws-The Revenge), countless imitators, and even the franchise's real-life impact on the public image of sharks, Jaws swims on through cinema.

And, on the 23rd November last year, Bruce came home, a painstakingly refurbished fibreglass prop, the fourth and only surviving model of the shark built for the film. Unlike his brothers, left to rot, or trashed in celebration of having finally finished the film, this survivor

hung by his tail for nearly two decades for countless fans to photograph at Universal Studios, before unceremoniously being dumped into a scrapheap, rescued and put on display over a dusty part of California and forgotten

about for another two decades. Resurrected by a long time fan whose love of the film propelled him into special effects work, he now hangs, pride of place, swimming forever thirty foot up in a museum run by the Academy of

Motion Pictures, the very people who passed over Jaws as Best Picture.

The shark may not have ever worked properly. But the idea of one sure did, a beast of music and suggestion

and suspense, terrorising sleepy American suburbia-on-sea, that even now shapes the very nature of multiplex cinema. Here he is, then. The last Bruce. This is the broken-down shark, the misbehaving animatronic, the legendary

creature heavy with meaning, and merchandise, and hype, and countless imitations. Here he is. That original "you're going to need a bigger boat,", you're-going-to-need-a-bigger-blockbuster movie star himself.

Here, swimming forever, dolls eyes and all, is that shark that changed cinema, forever.

Rating: Must See (Personal Recommendation)

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment