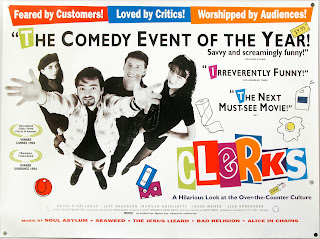

Micro-Budget March: Clerks (Dir Kevin Smith, 1h 32m, 1994)

Clerks can be regarded as many things. A film about films? Certainly; some of its most famous scenes discuss, in a pre-internet world, the untapped ephemera of pop culture, a vein that its director, Kevin Smith has steadily followed over the last twenty-five years, through high and low, from Chasing Amy to Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back. A film that captures the zeitgeist of Gen X as a bunch of disaffected slackers, drifting through life, unsure of their direction, their place in the world soundtracked by bands that lean upon precisely that? Certainly; few films of the period capture it, with the possible exception of Clueless, released a year later, better, and whilst that film explores the life of college students with a smart and wide-eyed sincerity, Clerks is altogether more cynical as it explores the yawning void after education. Heck, one could even read La Divina Comedia into this bizarre, purgatorial day of a dead-end job.

Clerks begins with one of cinema's great introductions-Dante, (Brian O'Halloran), toppling out of a cupboard into his messy bedroom, as he is called into work, a half asleep slacker whine to the voice, as he bemoans being called in on his day off. It's here that the visual style of Clerks makes itself known, the gritty, grungy high contrast black and white as much a stylistic choice as a necessity born of shooting much of the film, almost entirely shot inside the store at which Dante (and the real-life Smith) works, at night. Certainly, it lends itself well to the verité sense of the film, of this single snapshot in the life of its protagonist. Begrudgingly, Dante turns up to work, and here his troubles begin, with the locks jammed shut with chewing gum, forcing him to make a sign to remind customers that, in perhaps one of the film's most memorable visual, "I ASSURE YOU; WE'RE OPEN!"

It is, without doubt, the film's customers that form, such that the film has it, its narrative. Around them, in loose vignettes, we are introduced to Randall (Jeff Anderson), the clerk in the video-store next door, a fellow slacker who arrives late, spends much of the film in Dante's convenience store, and accompanies him on occasional escapades out of the store. Much of the runtime, though, is taken up with their discussions, as they pass the time between customers discussing everything from cinema to pop-culture to customer service to a remarkably frank discussion about how dead-end their jobs are, and how Dante lacks ambition. The relationship, as colleagues, friends, or simple acquaintances, is not only detailed, as the duo continue unseen discussions or refer to character we never see or hear from, but believable, and from this base, their later antics as they venture out of the store to play hockey on the roof, and most bizarrely to the (unseen) wake of a former classmate, spiral off in understandable escalations of boredom.

Against this well-established duo, a veritable cavalcade of oddballs, disaffected youth, bored and harried people and former schoolfriends shuffle through, and it is these strangers that give the film much of its humour. The film once Dante opens up-indeed, much of it is cut into these labelled vignettes-begins with a near five minute section in which Dante is slowly assailed by smokers and a lecturing salesman for gum, with the utter bizarreness of this situation slowly coming to the fore as a small gang of reprimanded smokers turn on the hapless store clerk. More follow, from a disgruntled customer of the video store, to figures that either contribute to, or are reviled or disturbed by the discussions between Dante and Randall, leading to a nigh punch-up between a customer Randall spits on and the hapless video store worker.

It captures, perfectly, the pure bizarreness of working retail, from the minor, including an offended man who overhears the duo's most profane conversation, to more memorable customers, including the mismatched duo of jock and distant friend of Dante who arrive late in the film to question what Dante is still doing in this dead end job, and to be unwitting party for the sudden appearance of a government official to slap a fine upon Dante for (Randall) selling a small girl cigarettes. Most memorable of all, of course, is that of a man who, as the most irritating of customers do, plays upon Dante's good nature to gain access to the toilet, lavatory roll, and finally pornography, and whose reappearance, dead, later in the film, highlights the biggest problem in the film.

For, whilst Clerks' irreverent tone lands in many cases, and some of the film's most memorable moments lean perfectly on crass sexual humour-the drive to the wake of their former school-friend descends, in hysterical tragi-comedy into a discussion of the death of a cousin of Randall's in bizarre sexual behaviour, during which the camera sits, a passive observer, in the back of Dante's car. When the film gets its sexual humour right, when it's at the expense of stupid, horny, sexually repressed men, when it plays smartly on the same vein of Gen Xer sexual neediness that fuelled Kurt Cobain et al out of Seattle to storm across MTV-powered-America, it's hysterically funny.

But when it comes to his female characters, aside from single-characteristic customers, the writing suffers. Kevin Smith has never been brilliant at writing women; Chasing Amy is testament to the overly male-focused world of Smith's cinematic universe, in which male comic book writers attempt to win over a lesbian artist, and Clerks is no better. Much of its plot, around Dante and Randall's misadventures, is full of what, at best, could be regarded as slut-shaming; not long after Dante starts work, his current girlfriend, Veronica arrives, and after a section where the duo lie behind the counter, they begin to discuss their sexual history. This, without what follows, is a remarkably frank, and equally remarkably well written scene; but, of course, Smith doesn't stop at this moment of shared frankness.

From here, the film tiredly walks through cliches of Dante's sexual openness being understandable compared to the number of blowjobs that Veronica has given, and, for all of Marilyn Ghigliotti's likeability, and indeed Smith's attempts to show Dante as an ungrateful and downright bad boyfriend, she is resigned to being a frankly rather boring and rather sexist caricature. This only develops further when, with the return of his former flame, Caitlin, (the late Lisa Spoonauer), she is essentially dumped by Dante, leading to a, in brutal terms, incredibly uncomfortable moment when she finally confronts her ex and storms out. That Dante believes he can fix this is, frankly risible, even as he boyishly stammers his way through this excruciating sequence.

This, though, is a minor thing compared to the treatment of Caitlin, which has aged like milk; the film suddenly introduces her midway through its central third, though her former relationship with Dante is hinted throughout the film as a whole, and his annoyance at her ending up with a designer becomes quickly tiresome, as he calls up the local newspaper to snoop out the details. This only becomes worse when she appears, and the film's gross-out humour finally tips over into absolute crassness, as she wanders off into the neighbouring toilet to freshen up, and finds what she believes is Dante, only to find exactly who she has been having sex with, in a frankly revolting moment that stabs to the heart of how tiresome, boring, and reliant on shock humour this film is. Caitlin is less a character, more a ill-thought out punchline.

This is particularly disappointing considering how well Smith can write, comedy or otherwise. Many of the film's set pieces are masterful; at one point, we cut to Jay and Silent Bob outside, Jay dancing to the hip hop music on his boom-box, only for the otherwise silent and stoic Bob to suddenly begin body-popping along with his friend. The film has too many great characters that are shot through with comedic sensibility, from the would-be Russian vocalist that lurks with the duo outside to the bizarre figure of a counsellor, who arrives to rummage through eggs in search of the perfect box, and the comedic set-pieces, from hockey on the roof to the duo legging it from the funeral home, back to their car as a small crowd chases. This is nothing to say of Jay and Silent Bob themselves, who steal every scene they are in, with Bob's sole line perhaps the film's most profound moment.

When this film gets it right, and so often it does, it is remarkable, a film that cuts to the very heart of an entire time period, a film that captures the zeitgeist of Gen X; the film's soundtrack stuffed with 90s alt rock and geek-core punk, the feel, the sense, the smell of the 90s. But more than this, Clerks works because it captures the feeling, the dead-end nature of working in retail, of the daily grind of waking up, dealing with difficult customers, and making the hours tick-by faster, trying to fit the minutiae of life around it. It works, simply put, because Smith captures this period, this yawning void of life after college, before marriage, perfectly, and in often hilarious terms.

One has to consider, however, just how impressive Clerks is as a piece of film-making. This is after a film largely based on Smith's personal experience, shot on a budget that combines insurance from a car lost in flooding, money loaned from Smith's parents, sold comic books and his tuition after he dropped out of Vancouver Film School. Its cast largely comprises hangers on, friends and family, from Mewes who went from tag-along to Smith-as-Silent Bob's talkative foil, to the chamelonic Walt Flanagan, a personal friend of Smith who plays no fewer than four different roles in the film, to Anderson himself, who attended high school with Smith. The film rests upon, and indeed uses these real-life friendships, to great effect.

Where the film truly triumphs, though, is in its tight production; it is, after all, a twenty-one day film, largely shot at night (hence the shutters being closed to avoid the obvious lack of daylight), with Smith barely sleeping during its production, and most of the cast and crew working in the day before shooting in the evening, in the very store he worked in. It is a film that marries experiences, with much of the film based upon Smith and a fellow friend's experience in retail, that strikes to the centre of the deadening nature of working in retail, with a ruthless, smart, and memorable sensibility, all of this brought to life in a film pared, via budget and deliberate choices to its very essence.

Clerks, in short, is the right film in the right place at the right time. It's easy to compare it to the other arrivals, particularly those from Miramax, but many of these, despite their smaller budgets, are still cinematic escapism, rather than what Clerks is at heart; a mirror to Gen X by Gen X, an anthem for disaffected youth, an anthem to being in your mid 20s, in a dead-end job, with no idea what you want to do with your life. No film feels like the suburban adulthood of the 90s, captures it as well as Clerks, from its fashion to its music, to even how its myriad characters speak. Whilst some of it hasn't aged as well, a throwback to a generation before, in tiresome sexual crassness that only occasionally hits the mark, in places it's as fresh, as irreverent, as wickedly funny as its ever been.

Over the last 27 years, Smith and Clerks have journeyed back and forth from the mainstream; the sequel and animated series have little of the charm, of that low-budget make-do-ness to them, whilst Jay and Silent Bob, that most off-beat of author avatars, have voyaged from stardom to the suburbs to perhaps the highlight of Smith's entire career, as sidekicks in a quest against the end of the world. With Clerks III approaching on the hindsight, perhaps a little part of Hollywood’s self-styled king of geeks, at a period where geekdom is not only the mainstream but is cinema and popular culture, will always be tied to Clerks.

But more than anything, it is the arrival of one of Hollywood's most original talents in a veritable triumph of a film, a grungy black

and white film almost entirely made in one location, and shot and acted by a bunch of 9 to 5 workers, teenagers, a couple of college dropouts, costing barely $28,000, that suddenly arrives on the scene and upends Hollywood. Whilst its gross-out humour and its ability to shock has faded over the last quarter century plus, it remains a hilarious film, and there is something disarming, something

utterly lovable about Clerks in its perfect encapsulation of dead-end people in dead end jobs.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment