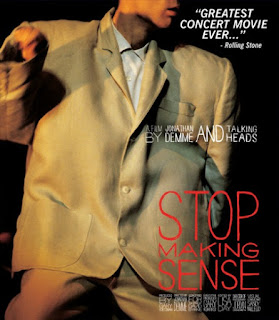

Music Month: Stop Making Sense (Dir Jonathan Demme, 1h 28m, 1984)

The concert movie is a strange beast. Of course, at the moment, deep as we are in the COVID-19 epidemic, all of us, with few exceptions, are seeing our favourite bands through screens big and small, as

our treasured artists appear before us in live-streamed performances, delve into their-at times gargantuan vaults, or release specially curated, intimately shot acoustic or solo performances. But as a medium, the concert movie

is, at its basest, a cheap and cheerful way to get up close and personal with our favourite artists in a way only highly expensive tickets or a great degree of luck and travel would grant us. One only has to look at the vast

cavalcade of filmed performances that bands-as-businesses like the Rolling Stones, Iron Maiden and Metallica, to name just a few release every year or so to get a sense that this is a colossally lucrative business. Otherwise,

they tend to be tantalisements, added to deluxe editions, collectors editions, obligatory such-and-such anniversary editions, to at least somewhat lessen the blow of their eyebrow raising prices.

There are of course,

outliers. Live at Pompeii sees Pink Floyd, on the cusp of recording Dark Side of the Moon, play through a titanic and suitably epicly scaled best-of set in

an abandoned, and oft-imitated Pompeii amphitheatre. Unstaged sees David Lynch and Duran Duran play off each other in a bizarre and spectacular way as Lynch's idiosyncratic visual style

overlays concert footage. Woodstock and The Last Waltz are colossally scaled sign-offs, one to the entire hippie era, the other to one of the greatest rock

bands in American music history, one featuring the great Martin Scorsese at bit-player behind the camera, the other coming smack in the middle of his peerless run of 1970s to early 1980s films.

And then there is

Stop Making Sense, a visually striking document, a beautifully vital piece of cinema in which the Talking Heads, at the height of their powers, push the very envelope of the concert movie,

matching a barnstorming greatest hits sets from Byrne, Franz, Weymouth and Harrison, and backing band, with hitherto unparalleled theatricality, staging, and, of course, one of music, if not cinema's most iconic outfits

in the form of Byrne's outlandish giant suit. It, simply put, is not simply a great performance, not merely a groundbreaking piece of cinema from how it shoots, edits, and indeed documents the band's music, but perhaps

the single greatest, and certainly most groundbreaking concert movies of all time.

By 1984, Talking Heads, without question, were one of the most popular bands in the world, from their humble beginnings as a New

York art rock band to taking on ever-increasing influence from world music, including the Afrobeat movement, spearheaded by Fela Kuti, with pioneering sound-maestro Brian Eno along for the ride, and an expanded live band, many who are seen in Stop Making Sense, brought on tour with them, adding an ever more complex and richer sound live. Taking a break between their pioneering record, and arguable artistic peak, Remain in Light, the band that returned to tour for their next album, Speaking in Tongues take an altogether more experimental visual style, from the bare-bones staging,

with no backdrops, few props and stark, almost severe light (an influence on tours as diverse as Nine Inch Nails' Tension tour in 2013 and Kanye West's Yeezus tour), not to mention countless parodies, homages and references, most notably to Byrne's iconic suit, in which

Talking Heads' performers and music speaks for itself.

This sensibility is present from the very first song (the band's early signature song, "Psycho Killer), onwards. Enter David Byrne, not in the

classic tracking shot beloved of the filmed concert from backstage to on-stage, but feet first. What builds over two minutes, from opening titles to the first shot of Byrne's face, is a sequence that, in one fluid movement

tracks up the musician, as a boom-box, one of the film's few props,is placed into shot, and, accompanied only by Byrne's iconic, idiosyncratic voice, and an acoustic guitar, proceeds to play a sparse, minimalist, almost

mechanical version of the backing track of "Psycho Killer". It's electrifying-Byrne, bobbing his head and tapping his toe to the music, that sense of almost uncontrollable, universal rhythm held in the form of

a skinny white cross-Atlantic man, is palpable throughout the film, from the first number of the last. The drum machine skips, and Byrne, beholden to its beat, twists and spasms with it, a moment that at once is spontaneous

reaction to the music and carefully choreographed homage to the death of the hero in Godard's Breathless.

Whilst all of Talking Heads and their aiders and abetters including

the late Bernie Worrell on keyboards and guitar, and the utterly kinetic, wild grinning figure of percussionist Steve Scales, it is Byrne, the vocalist, the talking head of Talking Heads, who is Stop Making Sense's star. It is his iconic, outlandish, oversized suit that is the emblem when he arrives back on stage for "Girlfriend is Better" practically draped in it. It adorns

the poster and live album accompanying the film-the one unmissable moment of this performance, a piece of clothing that practically defines Byrne in modern culture, from The Simpsons to Saturday Night Live. Certainly, of the four, Byrne is front and centre of shot for much of the performance, his lack of a guitar for multiple songs

taken advantage of in intricate choreography, from the aforementioned giant suit, in which Byrne's gestures, jerks and-yes, dance moves-are almost smothered, a man fighting against his clothing, whilst elsewhere, the preacher

persona of Once in a Lifetime, complete with strange, jerky, possessed movements are writ large without the distraction of myriad Byrnes or low-budget backdrop.

Yet there is no

sign, at least in front of the camera of that great schism of personality that eventually ended the band-Byrne leaves the stage at one point to allow Weymouth and Franz to thunder through their own group (Tom-Tom Club)'s

"Genius of Love", suitably enhanced by the full band, whilst one of Byrne's solo songs, "What a Day That Was" arrives mid-set, sandwiched between a Talking Heads deep cut, "Swamp" and then

newest single "Naive Melody (This Must Be The Place.) Perhaps the smartest single move of Stop Making Sense as a performance is the way in which the band members are introduced, first Weymouth to fill out the bass on "Heaven", then her husband Franz to add drums to "Thank You For Finding Me An

Angel", before finally the quartet are complete with Harrison on "Found A Job".

The cinematography echoes this-as more people join the stage, going from the intimate way that Bryne is shot, to the

wider and wider shots so by the time Talking Heads and their backing musicians arrive at "Burning Down the House" from the then recent Speaking in Tongues, it's in beautifully observed long-shots or takes that hold on a portion of the band for tens of seconds, Byrne by now sheened in sweat as he declaims vocals, acoustic guitar

in hand. From here, Byrne, together with his creative team, begin to explore, on the blank canvas of the stage, in the interplay of light and sound and musicians, the very act of playing live. "What a Day That Was"

is shot in eerie almost-dark, the band lit from below in a sinister, horror aping sense, that at once brings to mind German Expressionism and Hammer Horror that juxtaposes oddly yet perfectly with Byrne's usual neurotic,

free-associative lyrics.

There is, unquestionably, something arresting about its use of space, of light, of dark. During "This Must Be The Place", a lampshade arrives on stage, and Byrne uses it, as bands

as disparate as Tool and U2 have used lightfittings in subsequent performances and tours, from bare hallogen bulbs hanging from above to vast spotlights, to illuminate and cast into shadow-there's almost the sense of the

Dada of this very ordinary, very plain lamp and shade sharing the stage, being in essence a performer alongside one of the biggest bands of the 1980s. And then Byrne, as the song reaches its afro-beat via New York art rock

coda, begins to dance with it, in a sequence that is as artistic as it is wonderfully innocent, the look of wonder on Byrne's face palpable.

It's here, having peppered both the hits and the deeper cuts of

their discography that Talking Heads finally, on their home run, lean into the "Greatest Hits" usually so synonymous with concert films. The next five songs, the next five performances are not only Talking Heads

at their most imperial, as they positively smash each song out of the park, supplanting even the intricate work of the album versions of "Once in A Lifetime" and "Cross-eyed and Painless" with pure exuberance.

Stop Making Sense, certainly, as much as it is pioneering in how a concert is shot and staged, is as much of a technical achievement behind the camera, since it marks the first time a concert was filmed with entirely digital sound, and this only adds to the vitality of the entire performance, every synth stab, every guitar lick,

every little touch of percussion and bass beautifully balanced into a, at times, colossal sense of momentum.

And, whilst the thirteen tracks (fifteen on the expanded uncut edition that, for brevity, leaves one

Tom-Tom and one Byrne song on the cutting floor) before take us on a journey across Talking Heads' discography, it is the final one-two-three punch of "Girlfriend is Better/Take Me To The River/Crosseyed and Painless"

that not only summarise the band best, that are not only some of the most vital and exciting and euphoric performances in rock cinema, but where the film breaks down the divide between you and the band. If you aren't bopping

your head, tapping your toe, or getting up and dancing to the pure energy of this, then you'll never get this band.

Byrne arrives back on stage in the suit. Much of the appeal, much of the iconography of the suit is in the long-takes of Byrne in full, arms and legs flapping the great drifts of cloth around him,

or a head almost absurdly protruding from ridiculously broad shoulders, at once a comedic, a hyper-stylised sense, of the 1980s suited businessman, a feeble figure inside overlarge, immaculately tailored clothes, and the overtly

traditional, the influence of Noh and Bunraku and other Japanese theatre in the billowing clothes, brought west and inflated to outlandish proportions. The suit haunts Byrne-we've seen him share it with Homer Simpson,

seen Kermit, in a miniature version, flail about to a song older than a good chunk of its audience. It's refracted down the years. It, and Byrne are indelibly linked. For the generations since, Talking Heads is this curious

figure, dancing with, against, and in this suit.

It overshadows the final two numbers. Here, Talking Heads are, simply put, spectacular, the sparse nerves of the original cover version replaced by widescreen maximalism,

the stage bathed in blue, and harsh upright stage-light. Among it all, Byrne, big-suit et al, dances, the rhythm incarnate, the camera dynamic. And then, piece by piece, over the groove that Weymouth and Franz lay down, as

Byrne scats, he introduces his dramatise personae, the red cap he puts on at one point the single, saturated point of colour in the middle of greys and blues. And the band crash back in, one last song on their setlist, riding

the groove all the way to "Crosseyed and Painless".

And something happpens. For almost the entire concert, for the entire film so far, the camera has pointed towards stage. As the band turn from guitar

led intro to the strut of "Crosseyed...", the band in full flow, we suddenly cut from front-on shots, long-takes of the band, riding the high of the groove to behind the band. And then we are out into the audience,

as the film intercuts, for the first time, the audience reacting, the audience dancing, the line between band and audience finally broken down. And then they are off stage, and the credits roll, and Talking Heads are gone.

The credits roll, ending as the film began, with the sparse drum machine and the stark stage.

Stop Making Sense stands alone in rock and roll movies. There have been more technologically

advanced films, films that represent their band's discography in the round more, more theatrical films that turn the stage into a theatre space, in which the lines between music and musical theatre blur. But as a pure

and simple rendering of a tour, of a snapshot in a band's history, it has no equal. It is a perfect piece of film, a perfect rendering of everything that Talking Heads was at the height of their powers; a band as much

at ease in the outlandish as the mundane, in the theatrical and the verité. And, in the centre of it all, David Byrne dances, uninhibited, in stark white light, in a giant business suit, forever.

Rating: Must See (Personal Recommendation)

Comments

Post a Comment