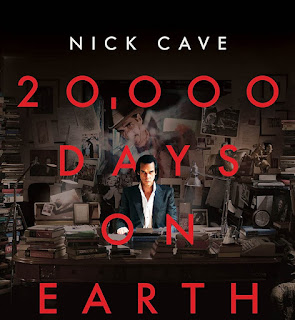

Music Month: 20,000 Days on Earth (Dir Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, 1h 33m, 2014)

It would be remiss not to use this music month to talk about some of my favourite musicians, but to do that in a cinematic form is somewhat of a mixed bar. We've already covered, after all, Some Kind of Monster, featuring Metallica, and whilst tour documentaries of, for example Japanese avant-garde metal band Dir en Grey, American Industrial Rock supremos Nine Inch Nails, or American Jazz leader, Kamasi Washington, are enjoyable for the keen fan, to the wider cinematic audiences they are curios at best. Nirvana and Iron Maiden are richer veins to dig into, but with the exception of Montage of Heck, more a film about the doomed Cobain than the band he propelled to fame and glory and the entertaining Flight 666, much of this once again falls into the realm of cinematic curate's egg.

Enter Nick Cave, Bad Seeds in tow. I have to confess, compared to some of my musical favourites,

I have arrived at the storied career of Mr Nick Cave and his various musical vehicles relatively late, just as the heady churn of adolescent music (heavy, stupid, fast, scares the parents) gave way to a modicum of sophistication.

Cave is no stranger to cinema himself; along with Warren Ellis, the duo have scored several films, most notably 2009's post-apocalyptic slog The Road, whilst his ability as a writer led to him writing and scoring 2005's Australian Western, The Proposition, and writing 2012's Lawless as well as the infamous rejected script for a sequel to Gladiator. Aside from bit-parts in various films, including as a musician in Wim Wender's Wings of Desire, however, Cave is a more elusive beast, only appearing in a major role in Australian drama Ghosts… of the Civil Dead in 1988.

Thus, 20,000 Days On Earth, a depiction of a quasi-factional day, Cave's 20,000th on earth, is a startling beautiful document in which Cave meditates on the nature

of creativity, rehearses tracks for the then upcoming "Push the Sky Away", spends time with his family, his close friend and creative partner Warren Ellis, spends time at The Bad Seeds archives and with his therapist,

and, in three ethereally bizarre moments, speaks to three figures from his past and present whilst journeying between locations in his then home of Brighton. It is, simply put, a film that encapsulates, better than almost

every other documentary about, or indeed, by any figure in music, what makes them tick-what makes Nick Cave, this great Gothic king, the last great murder balladeer who he is?

7:00. The film begins with Cave in

bed. Forsyth and Pollard, throughout the film shoot Cave intimately-every furrough, every line, his strewn office, where the sound of his typewriter clatters as the camera pans across the room, and nowhere is this more notable

than in the film's intimately shot opening minutes, prefaced by, in the film's one hagiographic slip, the evolution of Nick Cave, from Australian youth to gothic infant terriblé with the notorious Birthday Club,

to the Seeds, to Cave's wilderness years lost to drugs and chaos, to his return, triumphant, as one of music's great singer songwriters. It's here that the first of the film's key themes, of Cave's many,

largely female muses, appear, as he, in the voiceover that the film returns to several times, discusses his relationship with his wife, and how this, like his previous relationships, becomes, through the prism of his lyrics,

subject matter for his songs.

The musician settles down to work, a colossal tableaux of books, posters, clippings, images and other curios spread out around him. 20,000 Days is a strange film to talk about in terms of pure documentary-Cave, together with Forsyth and Pollard wrote much of the film's script, and one is left, even in the sequences where the

Seeds and Cave appear to be working, the degree of direction, of perfect moments that just happen to have been captured on film. Is this what Nick Cave wants us to think he lives like, in a positively bohemian existence, in a house as carefully, artfully structured as his stage personality? Like Dylan Jones writes about the late David Bowie, how much

are we really seeing under the mask of Nick Cave? Certainly, whilst Cave's 20,000th day on earth is not meant to be taken at face value-the film's expansion, distortion and truncation of time makes this impossible,

not to mention its final sequence neatly intercuts the Sydney Opera House and Cave's Brighton-but its minutiae seem to exist in a perfect world of the magical realism that inhabits so much of Cave's work.

From

here, the film further expands on the younger Cave, with a meeting with British psychoanalyst and author Darian Leader interviewing Cave, with a television in the foreground for much of the sequence. Here, as few other music

documentaries are, the film becomes intimate, becomes almost, even for a musician used to digging deep into the darkness of the human heart and finding only more darkness, painful as Leader follows lines of enquiry, from Cave's

relationship with his father, with two appearances where incognito, the elder Cave came to see his son play, to his relationship with women. The screen plays silent witness, at one point footage playing of the clearly intoxicated

Cave on stage. This whole sequence itself is intercut with the Seeds setting up, of the whole songwriting process, of Cave's book of lyrics scored through and written over, as revelatory as anything Leader and Cave discuss.

Whether this is some intricately scripted moment, these moments of intense personal significance brought back to surface by Cave to suit the overall direction of the film, or whether these are genuinely verité moments,

it doesn't matter.

These two moments in essence set the sense of the film; these moments of Nick Cave the man, and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds the performers intersecting, either side by side or at cross purposes; the film

going back in these densely made ensemble pieces in which Cave's background, experiences, and 19,999 other days on earth are discussed, largely in the film's other great centrepiece, the Bad Seeds archive, where images

from his past are brought up like jewels from the deep mines of the soul, from images of the young Cave as choirboy or with his first bands, or of his current wife, to his personal anecdotes about his time in Berlin, or his

experiences with the legendary Nina Simone, which he recounts with Ellis.

In the other direction, the film covers the production of "Push the Sky Away", a record that marks the start of Cave moving away

from the raucous garage rock of previous releases to a more experimental, more skeletal, more downtempo sound that he has continued down since, the role of Cave as captain and leader of the Seeds absolute as he leads the band

through new songs, including "Jubilee Street", which resurfaces, from embryonic guitar riff to fully complete song that acts as spectacular finale to the film, together with live performances that shows the Cave

persona, Nick as gothic-cum-alternative icon, hands entangled with the front row of his adoring fans, or crouched on the edge of stage, singing, seemingly, to a single member of the crowd. A portrait of a commanding figure,

certainly, but far from untouchable.

And in the middle of the film, dotted as Cave drives his car from location to location, are these peculiar, and deeply affecting vignettes, as intimate and soul-searching as the interview cum therapy

with Leader. First, of all people, comes actor Ray Winstone, as the duo drive in rainswept Brighton , the sea in the background, as they discuss the idea of reinvention, of the immutability of being a rockstar, the nature

of being famous coming and going with Winstone's discussion. Indeed, the concept of fame is one that haunts the film; Ellis and Cave, in their discussion of both Nina Simone and Jerry Lee Lewis, are as much the adoring

crowd, in awe of their own icons as countless audiences have adored the Bad Seeds over four decades, acutely aware of the power that truly great performers have in transforming and transfixing their audiences.

As

Cave drives away from Ellis, his narration discussing the "strange collaborator creatures" that he allows into his rich tapestry of lyrics and music, so an unmistakable Germanic voice enters the car. The camera cuts

to a front on shot, and Blixa Bargeld makes his oh-too-brief appearance. If the film has one fault, it is in the absence of Cave's great partners in crime, of Bargeld and Mick Harvey, Harvey in particular largely cut out

of the story in which he was a major party, his acrimonious split with Cave between 2008's "Dig Lazarus Dig" and "Push the Sky Away" not only changing the very sonic nature of the band to a less aggressive,

more electronically led group, but clearly leaving its impact upon the rest of the group and his long-term friend and partner.

It's understandable that, as much as 20,000 Days on Earth is a film about Cave's life, of those 20,000 days, the film looks to the present, the cutting forward edge of the Bad Seeds, and the new record, but long-term fans may find

the absence of the great male relationships and friendships of Cave's life, with the exception of Ellis and this small nod to Bargeld, aside from archive footage is the one element that one could regard as a revisionist,

an authorial edit, of the Cave story, and the one fault of the film-intriguingly, an out-take, included in the film, is a far more revealling and inclusive moment, the one gap in Cave's armour, Cave's love and care

for his collaborator, revealled in full. Its omission is the one moment, the one flaw in this otherwise superb piece of cinema.

But at the heart of 20,000 Days on Earth is this enduring sense of this creative force, of a man at once kindling the tiny flame of his creativity from his life and experiences, each song a tiny fragile thing that Cave

and his collaborators breathe life into before sending it out into the world, capable of making, as in his recounted tale of a meeting in Berlin, a tiny moment of another man's life a moment of colossal, almost heartbreaking

beauty, a man who leads us, our listeners, into these moments of darkness and light, from the tiny to the sky-scraping, and a figure who towers above music, a great gothic colossus whose music is capable of filling arenas

and drawing colossal festival crowds, a man who holds huge audiences in the palm of his hand, in his tales of violence and murder and heartbreak, who, for forty years has led the Bad Seeds from strength to strength.

What

20,000 Days is, in comparison even to the most intimate pieces of cinema in abstraction, about famous musicians, is Cave in his own words, a creative force in the form of a man, aware that in, writing about his experiences, through his novels, his music, and indeed this film, he changes

them, freezes them in ink and lyrics and music, in photographs, in film. It is a meditation upon the creative process, about how Nick Cave is informed and moved and motivated to create artwork, what compels him to "prop

up" his songs up with his muses, his voice-over a soliloquy, the thoughts of a man discussing what makes his artistic process work.

And nowhere is this better realised than in the film's final moments,

as, effortlessly, the film juxtaposes Cave's walk to Brighton's seafront, and the Seeds playing in his home of Australia. It is, simply put, one of my favourite moments in cinema, cut to one of my favourite songs by

this strange beautiful scavenger of memory and poet of dark and strange goings, "Jubilee Street" that finally coalesces, finally touches down, finally appears in full. Above it all, Cave intones, in words I have

marked, in messy handwriting, on a flashcard blu-taked to my computer monitor, advice from one creative mind to myriad others:

"We cannot afford to be idle. To act on a bad idea is better than to not act at

all. Because the worth of the idea never becomes apparent until you do it. Sometimes this idea can be the smallest thing in the world, a little flame that you hunch over and cup with your hand, and pray will not be extinguished

by all the storm that howls about it. If you could hold onto that flame, great things could construct around it, that are massive and powerful and world changing, all held up by the tiniest of ideas"

Cave arrives,

transported thousands of miles in a simple cut, on stage, the crowd cheer. The Seeds play. Cave sings, and, as the song builds, from sparse little thing, as strings enter, as choir strikes up, as Cave's lyrics become more

abstract, more ethereal, as the footage begins, spectacularly, to intercut Seeds new and old, Blixa and Mick present, ghosts in the rear view mirror, performing, in perfect juxtaposition, as Cave sits down and plays the piano,

past and future selves blurring immaculately into one, the same gaunt gothic figure. The song fades, and Cave walks onto Brighton beach, stares out to sea as the camera pulls out, the strings overtaking the Seeds as we leave

Nick Cave, the sun rising above Brighton, on his 20,001th day on Earth.

There are few films like 20,000 Days on Earth. In hindsight, together with Once More With Feeling (2016) a raw depiction of Cave as father in grief following the death of his son, Arthur, and how this grief coloured and informed the Seeds' "Skeleton Tree", and

this year's Idiot Prayer, an intimate concert movie, shot at the heart of this great insularity, this great pandemic, form a rough trilogy, but even as a single piece of cinema, even as

a single snapshot of a performer, an artist, it has few equals, in its meditation on what it means to be alive and love and create and document the world around you.

Whilst its narrative may be a vehicle for this,

choosing artistic document over veracity, of the artificial deeper truth to the imposed narrative placed upon the minutiae of the creative by the necessity of editing, one is left with, as few documentaries do, of the sense

of Nick Cave, of Cave the idea placed before his adoring fans, of Cave the artist, and how he creates and what compels him to do so, and, of course, Nick Cave the man. 20,000 Days on Earth does all three. It is, simply put, an absolute fucking masterpiece.

Rating: Must See. (Personal Recommendation)

Comments

Post a Comment