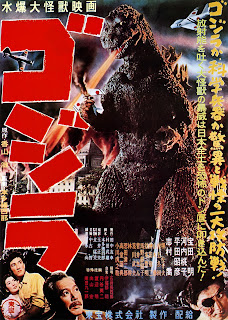

Under the Mushroom Cloud: Godzilla (Dir Ishirō Honda, 1h 36m, 1954)

No son of the nuclear age epitomises its changing themes, as Cold War thawed and froze, as the Doomsday Clock ticked back and forth, like Godzilla. Born of a nation barely a decade out from the horrors of Hiroshima

and Nagasaki, now struggling to make sense of further nuclear tragedy, Godzilla stormed onto the world stage as the nuclear made flesh, an-all destructive herald of chaos, whilst behind the scenes Toho, who breathed life into

this creature, would launch a boom in special effects, as the Japanese kaiju-monster movies would see tokusatsu (lit. special filming) grow in ambition, skill, and scale. Godzilla would return again, and again, and again,

his first era seeing him change from horrifying nuclear allegory to slightly goofy protector of the very nation he had laid to waste, before being returned back to natural menace in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.

The

most recent duo of films, Shin Godzilla (2016) and the upcoming Godzilla Minus One (2013) return the creature-now an icon and ambassador of the nation he's

destroyed so many times on celluloid-to his rightful place as nightmarish adversary of his home nation. Strip back sixty nine years, thirty eight films (including anime adventures, American escapades and the constant revision of his origin, appearance, and relationship with Japan), and one returns back to the original.

Godzilla/Gojira an often sombre, and undeniably political film in which, against the arrival and subsequent threat of the titanic creature's rampages,

our protagonists, Tokyo, and Japan itself are powerless to resist or to fight back, until, armed with a weapon as horrifying as the nuclear bomb, a scientist vows to destroy the creature, and Japanese special effects cinema

and science fiction cinema comes of age. This is the story of how Godzilla took Japan.

Godzilla is born of tragedy, and from the mushroom cloud, this one rising over Bikini Atoll, as part of the Castle Bravo test;

out of the hands of the Americans, and blown by unexpectedly strong winds, so the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon No.5 found itself in the middle of the fallout zone, its crew falling

sick, with one dying and becoming the first of many thousands of victims of the Castle Alpha and Bravo tests. Japan's anti-nuclear movement collected 30 million signatures (one in three of the entire population) before this movement coalesced into the The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Inspired by this incident, the nascent atomic

monster films, headed by The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), in featuring early stop-start by Ray Harryhausen, in which an ancient sea monster is awoken by atomic bomb tests and heads to-where

else-New York City, and the wildly successful 1952 re-release of King Kong, so Toho producer, Tomoyuki Tanaka had a brain wave.

His next film would marry the real life nuclear tragedy with the arrival of a monster,

originally gorilla-like, co-writing the film in a breathtakingly quick three weeks, barricaded in a Japanese inn, with writer Takeo Murata and writer director Ishirō Honda. Honda, a journeyman director who had directed

propaganda films, tourist documentaries for prefectures of Japan, acted as Akira Kurosawa's right hand man for Stray Dog (1949), and directed drama The Blue Pearl (1951) and anti-war war film Eagle of the Pacific (1953).Taking up the mantle of the monster movie, at this point named The Giant Monster from 20,000 Miles Beneath the Sea, because no other director at Toho seemed enthused by the project, Honda was drawn by his interest in science-fiction and an ideal director given his (in hindsight rather questionable) war experiences. Matching Honda would be Eiji Tsuburaya, already a veteran of Japanese cinema as a cinematographer

and innovator, now turned special effects guru-whilst Honda would deal with the human action, Tsuburaya was about to create an entire genre, as he shot the monster's rampages.

Godzilla begins with a painstakingly

accurate depiction of Lucky Dragon No.5, with a boat attacked and promptly sunk by a mysterious glowing patch of sea, the creature, Godzilla himself kept off screen-and indeed unnamed-until

nearly a third of the way from the film, sailors desperately attempting to escape or radio the mainland, with only a scant group of survivors picked up by another boat...which Godzilla also sinks, thus beginning (via Tsuburaya's

superb model work) a series of boat sinkings that only ends as the film shifts focus to Godzilla's next target. With survivors taken to the local island of Odo, so Tokyo begins to take notice, reporters arriving en-masse

on the island, with a ritual at the local temple tying the now-named but still unseen Godzilla to the area, though some of the younger residents of the island regard the creature as little more than a myth, only for the creature

to wreak havoc during the night, destroying houses (more model work by Tsuburaya).

Once again, as Honda will return to, time and time again, we see the human scale, the destruction of a house, the death of some

of the villagers in its collapse, and here the ominous durm und strung of Akira Ifukube's score, of low horns, the ominous thud of the passing creature, the panicked strings, turning the scene from mere b-movie moment

to tragedy, whilst, as John Williams will do with Jaws (1975) twenty-one years later, hinting at a creature the film is not-quite- ready to reveal. Yet. Shocked by the chaos, and with the

government finally taking notice as reports of destruction and fatalities, so Godzilla's other major theme, one that the series will carry with it for decades to come, rises to the surface-politics:

much as Anno and Higuchi juxtapose the political malaise post Fukushima with the arrival of Godzilla in Tokyo in Shin Godzilla, so here it represents their slowness, and ineptitude with dealing with the aftermath of the Lucky Dragon No.5 incident, and the deaths and disease that caused.

The Japanese

Government are largely dismissive of the threat, and send a token fact finding team to investigate, and the film kicks up a gear, introducing us to three of our main four characters. Heading the team is Dr Kyohei Yamane (Takashi

Shimura), with his daughter Emiko (Momoko Kōchi) and her boyfriend, and salvage ship captain Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada, who would go on to make several appearances in later Godzilla films). No sooner have they arrived

on the island than Dr Yamane has made a striking discovery-a trilobite, dozens of millennia extinct, alive in Godzilla's footprint, and no sooner has this discovery been made than the island's alarm bells begin to

ring. Godzilla has been sighted! Our heroes rush up a hillside, and over the top of it comes a head, colossal and reptilian, a pair of arms, and, as the villagers and investigation team make a hasty retreat, it roars, a strange and otherworldly noise created by a glove being rubbed up and down the strings of a contrabass. An icon has arrived in cinema, and the scale and power of the threat to our heroes,

and, as will become quickly apparent, Tokyo, has been made apparent.

As Godzilla leaves Odo Island, and heads towards Tokyo, so another theme becomes apparent, and one that will also become derigeur for the series

to come-the futility of the military-with Godzilla destroying much of the fleet following him, as they attempt to hit him with depth charges and with Dr Yamane remarking that the creature must have been awoken by atom bomb

tests, and is thus impervious to even nuclear weapons, requiring human study, rather than simply killing the monster, so the stage is set. To this, Honda adds one final piece, the troubled scientist, Dr Serizawa, who has been

working on a mysterious weapon that acts as an allegory for nuclear weapons, and whose small-scale testing of the said weapon, the Oxygen Destroyer frightens Emiko, forms a far more tragic figure, a dark reflection of those

men who built the atomic bombs and been haunted by their power. He is as much a representation of the nuclear threat as the encroaching form of Godzilla.

For. striding into view, comes the titular monster,

the perfect synthesis of Tsuburaya's special effects, from the creature itself, to the colossal tract of Tokyo, including several of its key landmarks that are steadily blown up, set on fire, or crashed through. Godzilla,

as a design is nigh flawless, a sense of solidity, a mixture of several dinosaurs given an eerily human gait, the jutting dorsal plates that he generates atomic fire from, and grasping clawed hands-far from a dumb animal,

there is, throughout his two rampages in the film, the unnerving sense of purposeful destruction, of a cunning cruelty to the creature. Much of this has to do with Haruo Nakajima's performance inside the detailed rubber

suit. Restricted as he is occasionally by its 100 kilo bulk-Nakajima could never lift the creature's left arm due to the suit's design- the suitmation performance is nevertheless impressive, every movement of the creature

given purpose, solidity, and a weight that only adds gravitas and realism to the destruction.

In barely fifteen minutes, Tokusatsu is born-Japanese special effects cinema will never be the same again, and countless

productions in the East and West have paid homage to its innovations. But Godzilla is not merely spectacle-the low angles he is so often seen from only emphasising his scale may dominate the sequence but there is nothing

gratuitous about his destruction, For long chunks of the destruction of Tokyo we see Godzilla's rampage at a human scale, and at a human cost, the camera following individual figures, or lingering upon, in truly harrowing

moments, on a family desperately trapped by Godzilla's rampage, or a TV crew trapped on Tokyo Tower as Godzilla closes in. Godzilla never lets us, unlike some many of its successors, forget the human casualties of the destruction.

The final shot of this sequence is a genuinely unsettling lingering moment, on

the destruction the creature has wrought-a horrifying echo of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki-that only becomes more harrowing once we see the casualties of Godzilla, the maimed and the dead, and in one particularly

dark moment, a small girl injured and bedridden, the crackle of a Geiger counter the only sound as it is run over her. Godzilla is nothing short than the horrors of the nuclear bomb come again, vengeful, unstoppable-the military,

in another moment that will become derigeur tradition for Godzilla, are completely ineffectual against the monster-and harrowing, an entire nation brought face-to-face with the bleakest part of its own history made flesh,

at once self-flagelatory and cathartic, destruction and victimhood. Godzilla is as much, like the Japan that bore him, a victim of the nuclear age, as he is arguably its most iconic creation, and his eventual fate is not a

moment of celebration, but one of sombre reflection, and a fear of Godzillas to come.

Nearly seventy years on, few films have the poignancy nor power, of Godzilla-it is a film from a nation barely ten years out from atomic attack, and barely six months after another brush with the horrors of nuclear weapons. Godzilla may have been many things in the

decades since, from anti-hero to openly good protector of Japan, to increasingly famous cultural export to, in 2015, cultural ambassador for the country he's destroyed dozens of times on film, but his first appearance

has lost none of its power, immediacy, and sombre majesty in the decades since, and no film out of Japan has been a more perfect parable for the nuclear age.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Godzilla is available to watch online in the UK via the BFI Player, and on DVD from the BFI. In the United States, it is available to watch online via the Criterion Player, and on DVD from Criterion.

Next week, we stay in Japan, but turn to the French New Wave, in a film that explores love in the wreckage of the nuclear age in Hiroshima Mon Amour.

Support the blog by subscribing to my Patreon from just

£1/$1.00 (ish) a month to get reviews up to a week in advance and

commission your very own review! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment