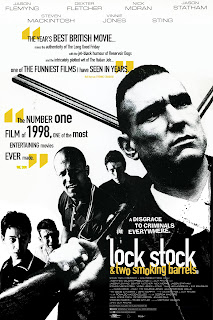

Gangster Season: Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (Dir Guy Ritchie, 1h 46m, 1998)

The British Gangster movie is a strange beast; to tell the truth, it’s something we will doubtless return to at some point, for British cinema and its potrayal of gangsters, and indeed the ever-changing

social fabric of the United Kingdom, are intertwined. It was thus hard to pick one-the 1947 adaption of Brighton Rock, that made Richard Attenborough’s careet, and typifies the genre post-war? Or maybe Performance, in which the Swinging Sixties meets the cold menace of gangsterdom in a film that peers into the darkening corners of the decade as it turned to the 1970s, and features perhaps the greatest

acting performance by any rockstar? Or perhaps even The Long Good Friday, in which the fears of the decade, from the IRA to burgeoning American influence in the UK, to police corruption and

the unseen rise of Thatcherism?

Certainly, for all these highlights, the British Gangster’s exploits are full of forgettable dross like the interminable six part Rise of the Footsoldier, the inevitable Krays (hi, Spandau Ballet), Bronson, Great Train Robbery and other historical events, the veritable Football League of “football

factory” hooliganism movies, or the downright diabolically bad gritty crime capers that crunch around nondescript areas of the UK with little local colour around the old ultraviolence.Believe you me, I’m not sitting

and watching Danny Dyer being “well ‘ard” in Stoke on Trent for two hours. Or indeed anywhere else. For every Carter, there’s inevitably a 51st State, for every Sexy Beast, a Clubbed, and Jason Statham and Vinnie Jones are everywhere, in a vaguely reassuring way.

Ah, but wait! Messrs Statham and Jones appear together

in Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, the epitome of Guy Ritchie’s fun, foul and frenetic style of East ‘Lunnen gangster escapades, inhabited by larger than life and often highly

psychotic figures and in which a quartet of friends lose it all in a stacked card game and must race against time, and against rival criminal outfits, to get the money before their untimely demise, stepping unwittingly into

a series of brutal turf-wars between criminally insane next-door neighbours, effusive and violently disposed porn barons and their menacing (real life criminal) assistant, middle class cannabis growers, and of course, the

one and only Vinnie Jones himself, their fate caught up with a pair of rare and valuable shotgun, in what, without a doubt is the strongest British directorial debut of the 90s, and one of its best crime flicks.

Thus,

enter Guy Ritchie. When not making a billion dollars remaking Aladdin for some reason, and when not losing about that amount with the puzzling King Arthur Legend of the Sword, The Man From UNCLE reboot and the exorable (and starring his then-wife, Madonna) Cast Away, Guy tends to make fairly decent, slick, and remarkably quotable gangster/crime movies. Oh, and two rather good Sherlock Holmes films, with much of the same stylistic eye. Ritchie is perhaps

the closest we have to a British Tarantino, although that comparison drops off once you get outside the comfort zone of quotable dialogue, non-linear story-telling, and local vernacular punctuated with lots and lots of four

letter words. Ritchie, like Tarantino, arrives onto the scene in the early 90s, with the short The Hard Case, attracting the interest of no less than Sting’s wife (Sting himself plays

a minor role in Lock Stock...), Trudie Styler, also responsible via Xingu Films for bringing Duncan Jones’ Moon (2009) to the big screen.

Ritchie, in all honestly, brings his style almost fully formed to the screen at once; we begin, like so many scenes in this film, with a con, and from here

we are introduced, selling stolen jewelry on a street corner, to Bacon (Jason Statham), in full patter, and Eddie (Nick Moran), a hustler, and card sharp; the duo are promptly chased by the “coppers”, as Ocean

Colour Scene crash in on the soundtrack-which is of course, and we are introduced, as the duo descend a staircase in slowmotion, the suitcase breaking open, via Alan Ford’s mid-London narration, to two of our protagonists-our

heroes aren’t the crime lords at the top-they’re not even the footsoldiers at the bottom-they’re four lads simply trying to scrape a living, and we’re promptly introduced to shopowner and wheeler-dealer,

Tom (,Jason Flemyng), and cook and law-abiding (if later revealed to be remarkably psychotic) Soap (Dexter Fletcher).

These four are such well-formed characters, given the first twenty or so minutes of the film

to bounce off each other, for us to learn how these men act around each other, that by the time the narrative places them under pressure, testing these small-time, but ultimately charming, crooks to their limits, they’re

such superbly wrought characters that we, like so many of Ritchie’s protagonists, as well as filling their mouths with some of the most quotable lines in late 90s British cinema, from the masterful patter of Bacon’s

opening montage that has more cockney than 90s American audiences had probably ever heard before, to the Samoan bar the trio wait in for Eddie causing consternation, to Soap’s knife obsession, (“Guns for show,

knives for a pro”), to the perfect encapsulation via the quartet’s back and forth of the English Lads’ Culture of the late 90s, complete with masterful use of profanity and often gleefully ridiculous nonsequiters.

We are also introduced, as the quartet pool their money together, to some of the local “colour”, from Greek wheeler-dealer, Nick (Stephen Marcus), and Eddie’s father JD (Sting, who is more than

a match for the other ‘ard men’ in this film) to the man that Eddie, an aspiring card-sharp, will be playing against, porn baron, and famously volatile “Hatchet” Harry Lonsdale (P.H. Moriarty) and his

henchman, Barry “The Baptist” (real life hard-man and notorious East London bouncer, boxer, enforcer and all-round personality, Lenny McLean, who died shortly before the film’s release). Together with sundry

middle class-drug dealers, Northern thief duo Gary and Dean, and Eddie’s volatile next-door neighbours (led by Dog, (Frank Harper) and the weasely Plank (Steve Sweeney)), and equally dangerous East End crime boss, Rory

Breaker (Vas Blackwood), the film sets about pitting these pieces against each other, holding its trump card back till later

The film wastes no time in getting down to its central conceit-that the cardgame is

rigged, a series of slickly done hands seen through security camera and transmitted to Harry via bizarrely complex morse code device, Eddie is soon lulled into a false sense of security, and

into ever larger bets, with Harry offering to lend him the money, only to close the trap, and leave him and his friends owing him half a million pounds, the stunned Eddie’s exit done wonderfully in a series of dazed

double, or occasionally triple exposures overlaid as he steps away from the table to throw up outside. At the same time, Harry has gone for another play, sending bumbling and roundly idiotic thieves Gary and Dean to steal

a pair of antique guns, only for this (intercut with the card game) to go south, the duo nearly getting shot, and making off with the contents of an entire gun cabinet, only to fence the two

most valuable to Nick.

Knowing the quartet simply do not have the money, Harry issues an ultimatium-pay within a week, or start losing fingers, and eventually, JD’s bar, and it is at this point that the film

reveals, positively reveling in it, its ace in the hole, its secret weapon. Vinnie Jones, playing Big Chris, the first of a veritable army of nigh-unstoppable East End ‘ardmen, was already a known quantity to the lads

culture of the 90s as a hard-tackling, no-nonsence player for, most notably, Wimbledon FC, and a key part of their infamous “Crazy Gang” His character Big Chris, in simple terms, is the immovable object at the

centre of the film, a mix of Lone Wolf and Cub’s father/sword for hire and Ghost Dog’s gangland enforcer with his own moral code. He gets the majority of the best lines, undeniably made his career in this movie, and moves through it with incredible purpose and presence,

from beginning to end, whilst protecting his young, if not entirely innocent, son, and attempting to protect his livelihood.

It is here, threatened with mutilation and lost livelihoods, that the quartet stumble

on some good luck, overhearing Dog and his gang planning to rob the middle-class drug producers in their own factory, and begin to plan their own heist against the murderous gangster, procuring the two guns from Nick in the

first of many twists of fate that run through the entire film. Dog’s heist also begins to bring another great strand of Ritchie’s cinematography, that of the farce-the heist is a disaster that seems to careen between

set pieces, from being unable to open the door to one of Dog’s men getting shot with his own (semi-automatic) gun by the drugdealer’s female companion to the kidnapping of a traffic warden (a pre-fame Rob Brydon),

and getting back with the loot only to be relieved of it by Eddie and the boys in an equally chaotic moment. Nevertheless, our heroes have come out on top, despite making a nigh-fatal enemy of the utterly deranged Dog.

The

quartet attempt to fence the drugs via Nick, only for his buyer to be the very man who owns the operation, the enjoyably violent and ruthless Rory Breaker-making it a damn shame that, unlike

Jones and Statham, Blackwood never quite made his breakthrough in the same way-who proceeds to declare war on the thieves, forcing Nick to give over their address in a brutal dressing down, whilst, frustrated at being unable

to locate the thieves, Dog unexpectedly comes across the listening devices the quartet have been using to listen in, and vows revenge on them, breaking into their house and finding the money, guns, and drugs, as the quartet

party into the morning, they thus manage to miss a brutal shootout between Dog’s gang and Blackwood’s heavies that ends with only Dog and the drug dealer alive. The hapless gangster is quickly relieved of his cash

in a brutal and efficent fight against Big Chris, who returns the guns, and hands the cash to Harry.

Our quartet soon find Eddie’s house almost destroyed, and still filled with the corpses of their would-be

killers, and head to Harry’s, only to find-in perhaps the scene’s most blackly comic moment, that Harry and Barry have been shot dead, and in turn killed Gary and Dean, Most of the quartet make off with the money,

leaving Tom to deal with the gun, only for fate to once again twist, as Big Chris, having been carjacked by Dog, with his son as a hostage, crashes into the trio’s car, brutally deals with Dog, and then takes back the

cash, reappearing once the coast is clear, and our heroes have been cleared, to present them with a catalogue that identifies the two shotguns as worth hundreds of thousands each-with one final twist in the film-that Tom has

already gone to dispose of them-we end, thus, with our heroes desperately trying to contact him as he hangs from the bridge, phone in his mouth and guns in hand.

Lock Stock.and Two Smoking Barrels is an enjoyable romp of a film, a snapshot of a certain era of British culture, at the tail end of Brit-pop and lads culture, shot through with a blackly comic sense

of humour, a certain quotability, and a slickness that utterly hides that the film cost under a million pounds to make, and largely eskews the setpieces of higher budget movies for a stylistic comedy of errors. Thanks to-of

all people-Tom Cruise, it hopped across the Altantic, made the careers of Statham, Ritchie and Jones, and, for the first two, propelled them to superstardom (if occasionally punctuated by returns to their old Brit Crime Drama

proving grounds). Perhaps more than any other country’s take on it, the British gangster movie, at its very best is a zeitgeist, a perfect capturing of the spirit of the times. Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels is such a film, a gleeful joyride of a picture in which our intrepid, if not entirely innocent quartet of likely lads must stay alive in gangland London, save their

skins, and, against the odds, make good in one of the best, and most fully formed directoral debuts of the 90s.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.00 (ish) a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment