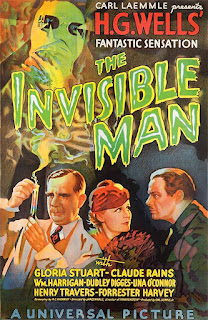

Famous Monsters of Filmland: The Invisible Man (Dir James Whale, 1h10m, 1933)

The Invisible Man, compared to his peers, is nigh-invisible on the big screen. Compared to the monsters of the films that we have already covered, Griffin (most famously played by Claude Rains), is a comparatively minor player in the Universal Monster Squad. Dracula, Frankenstein and Imhotep have had dozens of adaption, reimaginings and reboots, and have practically become shorthands for their archetypes. The Invisible Man, whilst iconic in his own way, has eight films; this, the original, three sequels with variable connections to the original film, three comedies, and the impressively taut 2020 reimaging that stepped out from the wreckage of the Dark Universe, plus a few cameos in children's animation and a brief appearance in the roundly dreadful The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

It's slim pickings for a character whose first outing still remains a remarkable entry in not just Universal Horror, but the genre in general. This is, after all, not just a film that, by the very nature of having an invisible, (and vengeance set) protagonist, pushed the technical innovations of cinema to nigh-breaking point to allow Griffin to reveal his invisibility to his victims and allies, made the career of one of the great actors of the 1930s and 1940s, in the form of Rains, but also takes the idea of the Universal Horror monster in a very different direction, that of a very human, and very dangerous foe as Griffin becomes not just our monster, but our protagonist, in the most unique film of the Universal Monster ouvere, and undeniably its most overlooked.

We begin, once again, in the aftermath of Dracula, with Carl Laemmle's team once more turning once against to the world of literature to find inspiration-whilst Laemmle and Laemmle Jr turned to Shelley's Frankenstein, Universal then proceeded to option the rights for HG Wells' 1897 novel, The Invisible Man-a first for Universal's Monsters, in that Wells was still very much alive (although the first adaption of Well's work comes a year earlier in 1932, with the first of many adaptions of the Island of Dr Moreau). Alongside it, the studio also bought the rights to a similar, if altogether more violent and gory, invisible man story, 1931's The Murderer Invisible. There was just one problem; the film's only crew member was Boris Karloff, and he was soon off to MGM to shoot the (in hindsight undeniably offensive and dated The Mask of Fu Manchu).

So, for about a year, the film essentially gestated, going through a number of directors; first, Robert Florey, who co-wrote the film with Garrett Fort, a co-writer of Frankenstein and Dracula, envisioned a film largely along the lines of Murder Invisible, full of violence, including blowing up Grand Central Station and invisible animals (including an octopus!) The script, unfortunately, took too long, and Karloff and Whale go off to make The Old Dark House (1932). What follows is a cavalcade of writers, from John Huston to Richard Schayer, to even the stalwart Balderston, who, by this point had written three scripts for Invisible Man movies, culminating in Preston Sturges, later to be practically the inventor of the screwball comedy, setting his version of the film in Russia, where the roguish invisible man has his revenge on Bolsheviks. He is promptly fired a day after handing in his script.

Moreover, by this point, despite the glut Universal had recieved by making Frankenstein and Dracula, the studio was also leaching money badly, causing the studio to essentially shut down for three months, to reopen in May. By this point, Karloff had left the picture, Whale's own script had been rejected, and Whale had reunited with R. C. Sherriff, the author and original screenwriter for Journey's End, via which Whale had made his reputation. With Wells agreeing that the film's narrative sweep would be much better with "an invisible lunatic...mak(ing) people sit up in in the cinema more quickly than a sane man". As the lunatic, as Griffin, Whale casts Claude Rains, an actor he's previously seen in London, despite Universal encouraging him against this, and despite Rains, in hindsight, being difficult to work with. Around him, the cast are largely Whale's regulars (Gloria Stuart, who plays Griffin's love, Flora), actors known to work well with Rains (William Harrigan), or, for a number of smaller roles, actors on the verage of becoming famous. (Walter Brennan and John Carradine).

Rains, undeniably, is this film; we are itnroduced to him arrviving out of the snow, swaddled in overcoat, and hat, and his arrival in the village of Iping is a wonderfully atmospheric moment, arriving amongst the hubbub of the country pub to shock its inhabitants into silence-more is to follow, as the film takes its time building up the intrigue of whom exactly this stranger is, why he demands to be left alone, and what his strange garb and experiments are for, doubly remarkable given the brevity of films overall in this era. The reveal, though, of the Invisible Man, is one of the finest scenes in horror cinema, and something the 2020 remake apes to great success-having been stumbled upon by the publican's wife, and having set upon the publican after having been told to leave, Griffin now faces off against the angry villagers, and, after failing to remonstrate with them, reveals exactly what he has become.

It is here, as the invisible man shucks off his clothing, disappears before our eyes and begins to terrorise the village with a series of violent japes and assaults, that the film's masterful use of then-cutting edge special effects come into play. It may seem crude (especially since remasters have revealed much of what made the effect work in the first place-a series of matttes that required Rains to wear a bodysuit in an early and primative example of greenscreen, masterminded by John P. Fulton), but there is something undeniably effective-and terrifying-about the idea of a man becoming invisible. We see the trail of chaos he wreaks, as he laughs manically, strips, assaults those in the room with him, escapes, and proceeds to terrorise the village, all whilst cleverly hidden wirework and the mattes show him interacting with objects he destroys and people he attacks.

Even if this was the focus of the film, the mixture of Rains' performance and Fulton's special effects would more than make this an effective short, with Griffin's growing rage and frustration giving way to his reveal and violent retribution. It is, essentially, the film in miniature; Griffin soon arrives at his friend and colleague Kemp (William Harrigan)'s house-Kemp is already aware that Griffin has been experimenting with invisibilty, but the scene between them, as Kemp becomes slowly aware he is no longer alone, the menace that Griffin brings to the character and the horrifying power he holds over his fellow man with his invisibility only compounding just how superb Rains has to be as a character that we never see the face of, is often simply not on screen, or having to work alongside a series of special effects to bring the character to life.

That Rains is able to create such menace with just his voice and body language is nothing short of spectacular. What is absolutely clear by this point is that Griffin is quite mad-his former colleagues putting this down to the chemical monocane, that the scientist has used to fulfil his transformation-and Griffin quickly forces Kemp to be his accomplice in a series of murders and acts of violence that will see the duo take over the world. This begins with Griffin wreaking his revenge on the village that, by now, has been enveloped in a police enquiry, and where Griffin's research is still kept. Griffin's rescue of the books with Kemp as getaway driver soon turns violent, as he overhears the policeman in charge say that his crime spree is nothng but a hoax, leading to Griffin murdering the officer in brutal and effective fashion, and making his escape.

This not only provokes Kemp into calling both the police and his colleagues, including Canley (Henry Travers) and his daughter, Flora, but causes the police themselves to start a colossal manhunt for the invisble murderer-here, we do see at least a little of the man under the monster, as Griffin calms down notably around the woman he loves-but this soon gives way to cold vengance, as he realises Kemp has betrayed him, and vows to kill his former friend at 10 pm the next day. Griffin proceeds to wreak havoc, derailing a train in an impressive model shot, steals and throws away banknotes, and kills two of the volunteers searching for him, only to return, and despite the heavy police protection, and the many traps their commander has set in place, Griffin makes good on his threat, having trailed his former friend all day, and consigns his colleague to a firey death as his car is sent careening down a slope and off a cliff, in another impressive bit of model work.

By now, though, the police have caught up with Griffin, and after attempting to shelter in a nearby barn from a snowstorm, he is discovered by a local farmhand, the barn is set ablaze, and attempting to escape, and given away by his footprints, Griffin is shot, and, dying, is brought into hospital, where, in front of Flora, he admits his mistake in meddling in things outside of human knowledge, and, dying becomes visible once more, a downbeat, but fitting end to the character, that ends the film once again with the decisive victory of the man against the monster, but at a far greater cost than before. For all his malovelence as the Invisible Man, it is the love for Flora that wins out over his destructive plans to take over the world-that this comes as a warning, rather than as a moment of redemption, though, only underlines how dark this film takes the Universal Monster formula.

Perhaps we've been unkind to the Invisible Man's influence; it is, after all, one of the favourite films of horror giants John Carpenter and Joe Dante, writer Kim Newman, and the late great Ray Harryhausen. It is, undeniably, still remarkably effective as a piece of cinema, and has some undeniably innovative special effects that would be an important step on the way to creating an entire way of making characters partly (or indeed entirely) invisible, which in turn would further influence the fields of mocap and being able to digitally replace entire actors with computer generated characters. It is still a superb film, topped by a spectacular performance by Rains, it is still a wonderfully taut thriller and a worthy addition to the Universal Monsters pantheon, but perhaps most of all, like its protagonist, its greatest influence is felt by its unseen, but undeniable influence on horror and special-effects cinema in the decades since.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.00 (ish) a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment