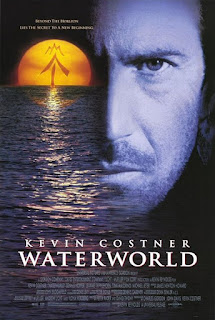

Back From the 90s: Waterworld (Dir Kevin Reynolds, 2h 15m, 1995)

Waterworld is synonymous with failure. Its spectacularly overblown $175 million budget (adjusted for inflation, the 12th most expensive film of all time), and subsequent financial failure, despite being the 9th highest grossing film of 1995, places it in a rather unesteemed camp; that of films that have become a shorthand for being colossal financial bombs. There it languishes in the company of Heaven's Gate (1980), the thunderingly bad Ishtar (1987), the aforementioned Cutthroat Island (1995), and the unholy trifecta of Mars Needs Moms (2011) John Carter (2012) and The Lone Ranger (2013). Together with the staggeringly bad The Postman (1997), it left the career of one of the 1980s biggest stars, Kevin Costner, dangling by a thread, and its director, Kevin Reynolds, the man who brought us Robin Hood Prince of Thieves and the cult Fandango, making utter pap like 2006's insomnia-curing Tristan & Isolde and sub-par sword and sandle flick Risen.

And Waterworld deserves none of this, none of the twenty-seven years of withering putdowns and reductions to a punchline of a Hollywood that have gone on to grander, and even more insane losses in the intervening years. For, whisper it, not only did Waterworld never actually truly deserve the title of box-office bomb, but Waterworld was never a bad movie in the first place. It may well have been subject to a troubled production, that borders on the completely insane for the pure scale of the film, and its reliance on being shot on the open sea, a bloated budget, studio interference, and the collision of absolutely titanic egos-none of them somehow belonging to co-star Dennis Hopper-but Waterworld is a good film-arguably a great one. What went wrong? How did one of the great action movies of the early 90s sink without a trace? Does it deserve to be more than a film that took years to break even, and a moderately successful theme park stage show? Is water wet?

By 1994, Kevin Costner and Kevin Reynolds (the two Kevins, as I'm going to call them this review), had had a professional relationship and a personal friendship for close to a decade, Costner first coming to prominence in Reynolds' 1985 film Fandango, advised Costner and acted as second unit director for Dances With Wolves, before launching both of their careers (and, undeniably, that of Bryaan Adams) into the stratosphere, with Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). Moreover, the rest of the early 90s was an undeniably superb run of films critically and commercially for Costner, with, almost back to back, JFK (1991), The Bodyguard (1992), and A Perfect World (1993) cementing the actor as a major figure in Hollywood, and a major box office and critical pull.

It seemed, in short, idyllic. However, with Wyatt Earp (1994), largely overshadowed by Tombstone, and with Reynolds' historical picture, Rapa Nui (1994), produced by Costner, barely making back $300,000 on a budget of $20 million, stormclouds were beginning to gather over the duo, as they looked for their new project. What they found, via a script by Peter Rader, and David Twohy (who would later go on to direct the majority of The Chronicles of Riddick and write the script for GI Jane), is Waterworld, a concept that, by 1994, had been in production for over a decade, but that, with the growing threat of climate change, with the forerunner of the Kyoto Protocols, the UNFCCC, signed in 1992, had become increasingly salient, with its world drowned under melting ice-caps.

Originally intended as a mere rip-off of Mad Max (with apocalyptical setting, grungy, cobbled together technology, and a lone hero chased by nefarious forces whilst protecting a child), the film gathered influences from the Old Testament and Homer's Odyssey. Here things get, if anything, more convoluted, with the film owing an undeniable debt to pulp comic story Freakwave (1983-84), co-written by Peter Mulligan and Brendan McCarthy, the latter of which would go on to co-write Mad Max Fury Road-this connection to Mssr Rockatansky only deepened by the presence of Dean Semler, the cinematographer for Mad Max The Road Warrior. With the stage set, (including a colossal, multi-million dollar archipelago, and two, fully functioning-and one fully transforming-trimarans), so Waterworld set sail, with a budget of $100 million.

It is the 25th century, and thanks to a quick fade from the Universal Logo to the submerging Earth, with only tiny sections of the world still above sea level becoming the mythical Dryland, so we are introduced to The Mariner (Kevin Costner), a mutated "Ichtyus Sapiens", a near-human creature that has evolved since the Earth drowned, with mutated hands, feet, and gills (created via superb prosthetics). Our hero is quickly fleshed out in a superb opening setpiece, where he finds himself, midway through a salvage operation that shows off his technologically advanced boat-an entirely real and colossal practical effect-, and his preternatural swimming ability, as he leaps off the back of the boat, into the seemingly endless ocean.

Surfacing, however, he finds himself face to face, and quickly tangling with a fellow seafarer, who quickly becomes unmasked as a thief. Confronting the seafarer over his theft of the boat, and the fruit from the Mariner's prized lime tree, so the two argue, the seafarer telling the Mariner that the nearest atoll (the last bastions of humanity) is twelve days sailing away. They proceed to bicker over the value of this information, until the Smokers, a gang of petrol-hoarding ruffians, later to become the film's villains, come into play. The Mariner's boat suddenly converts into a highspeed yacht, and, gathering speed, not only collects the salvage, but destroys the sail from the thief's boat, leaving him to be picked off by the Smokers, as he sails on. The sequence has lasted barely five minutes, and in it, we have not had our hero outlined as a tough, and solitary figure with both ruthless and resourceful streak, but the harshness and hostility, and doomed sense of the world around our hero.

Arriving at the atoll, here, the film rapidly fleshes out the setting out further, with the Mariner granted access, and his precious dirt, one of the scant reminders of Dryland, prized and given a hefty reward, which the Mariner uses to buy water, and a tomato plant. Both, introduced and stowed away by the Mariner as he returns to his boat, are emblematic of the rarity of freshness in this world where even corpses are recycled for their nutrients, and where interbreeding is beginning to severely affect the remaining human population, huddled behind the walls; this is a humanity in decline. Moreover, with the encroaching forces of the Smokers, represented by their agent, The Nord (played by a scene-stealing Gerard Murphy), who lurks in this early section of the film, so there is a sense of these small oasises of calm living on borrowed time.

Out of this, though, the film introduces its two innocents, Helen (Jeanne Tripplehorn), who works as a shopkeeper, and her young ward, Enola (Tina Majorino), who carries a tattoo of what is rumoured to be a map to the mythical Dryland on her back. They, and indeed the Mariner are about to make their escape from the when a mixture of bungling accidents and the Mariner being unmasked as a mutant, and locked in a cage, from which, glowering, the Mariner rebuffs attempts by Helen's ally, Gregor (a scientist and aeronaut, played by veteran stage actor, Michael Jeter), to rescue him. His execution in the same mire that they recycle their dead in is, however, shortlived, for over the horizon come, in force, the Smokers, and from here the film not only gains its best asset, but seems to leap up several gears in terms of its action and drama, as the Smokers close on the atoll.

The Smokers themselves may simply be the junk-driving, violent, lawless, and fuel-obsessed figures of the world of Mad Max placed into water, but with them, they bring an undeniable heft to the story, and a perfect foil to the Mariner. Their appearance is, undeniably, spectacular, rolling in out of the sea, en mass (a shot that feels like, in turn, it influenced the arrival of Immortan Joe's warparty in Fury Road), their forces pummelling the atoll. With the sequence introducing a dizzying number of waves that almost beleague the viewer with the power of their motley forces, from half-mad gunners who blow their way through the doors of the atoll and decimate those to waterski ramp and waterskiiers who leap over the battlements with the assistance of a plane. That Reynolds and Semler manage to keep this chaos, especially once the Smokers get inside the atoll, in frame, and remarkably coherent, is nothing short of a miracle and it is hardly suprising that these action-packed sections of the film made the leap to the stage show, packed with stunts and daring do as they are.

Amidst the chaos, the Mariner is rescued by Helen, from the mire, and he is eventually convinced to protect she and Enola, as their other route out of the falling town proceeds to accidently take off. Making their way through the chaos, as bodies, and the very structure of the atoll, fall around them, the trio begin to make their escape, and it is here that the film pulls its trump card, in the form of Dennis fucking Hopper. Hopper makes this movie, from his very first appearance on screen, to his explosive demise, The Pastor, as his character is called, is little more than a one-note villain-his main drive is to use the map on Enola's back to find (and presumably usurp) Dryland, but Hopper brings, as he undeniably did with King Koopa in Super Mario Bros, a certain energy, that leaves him electrifying and frankly, the best thing about this film.

Unfortunately, as soon as the film introduces him, he's blown up in our heroes' escape, and whilst he'll resurface in about twenty minutes, sans eye and with a suitably waste-landish eyepatch to match, we are now stuck on the ocean with a standoffish Costner, and his charges, who spend the next section of the film bickering with him, or in the case of Enola, simply doing endearing (at least by the director and writers' judgement) things, whilst the Mariner grumbles about having to take them to the nigh-mythical Dryland, and having to provide for someone other than himself. It is here that the film flounders, completely out of its depth-not to lay the blame entirely on Costner, but his performance throughout the film comes across as merely uninterested rather than standoffish or hostile. Even in sequences where he is meant to be angry-the escape damages the boat, he barely changes, other than to glower a bit more, or to cut Helen and Enola's hair off to make ropes.

When the Mariner inevitably turns full action hero in the film's final third, it's utterly believable-hell, it's where the film feels its best, its most original, compared to the reluctant Max of the films these films co-opt so much from. Costner, undeniably, is having fun, a veritable one man army ruining the Deacon's plans, and blowing up his base, the ruined Exxon Valdez. When the Mariner is doing things to protect Helen and Enola, he is a well-played hero, with an unerring sense of history and danger about him. Here, in the cinematic doldrums between action setpieces, with Costner having to act anti-heroic, it is excruciating. His entire performance is leaden, dull, and Costner comes across as a completely unlikable character, needlessly so, given how harsh the world around them is, especially given how powerless women are seen to be through the world's development, especially in the case of Enola, who's little more than a prize for the Smokers to snatch away. Worse, Costner has to speak, and he barely breaks from an irrritated whine for the majority of the picture

It is this that is undeniably the bellweather of the film, where its production problems, where Costner's ego, where the film's incredibly episodic structure, where Costner essenitially ends up as defacto director after Reynolds walks off set, because their vision of the film is at such odds, and where script-rewrites by Joss Whedon esseially crowbar ideas from Costner in wholesale, and the bizarre and calimitous decision to shoot an entire, already eyewateringly expensive film, on open water comes home to roost. Being with the Mariner outside of the action scenes and the final third of the film is arduous, his character development comes in erratic stops and starts that seem to be more tied to how many action setpieces the film has-at some points it practically goes into a holding pattern before a new foe arrives on the horizon

Whilst you can't help but welcome the reappearance of Hopper and his goons, or an incredibly dated CGI sea monster, or a needlessly creepy, paper-and-sex-obessesed mariner (Kim Coates), it almost feels like these sequences are inhabited by another, far more capable and audience-pleasing character played by Costner, who just happens to utterly resemble the Mariner during the quieter scenes. The other, more notable problem goes far deeper, and hamstrings the entire film. Not much happens in Waterworld. Our hero arrives at the atoll, meets his cargo to be, rescues them from the Smokers, sails around for a bit with a vaguely damaged boat, realises his charges are hungry, catches a fish, runs into said creepy trader, eventually kills him, is found by the Smokers, engages in a fun setpiece with Jack Black's pilot, and soon find that Enola's pictures may well be of the true Dryland.

Helen and the Mariner descend to the sunken world below, pop back up to find themselves surrounded by The Deacon and his forces, who kidnap Enola, the Mariner gives chase, rescues Enola, blows up the Smokers, and find Dryland, only for him to head back out to sea, his true home. That's not an abbreviation. That is every major event that happens in this film. As a result, it's a tonal whiplashing mess-one minute the film is charging along at top speed as the Smokers hunt our heroes, then the next, the film seems to bog down in miasmic dialogue that does nothing and goes nowhere. It's like the Mad Max films being occasionally interrupted by discussions of why Max feels so lonely and that if he had friends in the post apocalyptic wastelands, he would be less alone. This lack in confidence in the film's action, through showing, rather than telling, is what fatally wounds the film.

This in itself frustrating because for great chunks of the film, Waterworld is one of the best action movies of the 1990s. In motion, when the chaos and waves and explosions roll past camera, where Costner doesn't have to speak, where Hopper grins maniacally, or praises the patron saint of the Smokers (the actual captain of the Exxon Valdez), or even when the film's environmentalistic message rears its head, the film is spectacular (It's still bemusing how overtly environmentalist action movies are this, 2004's The Day After Tomorrow and the astonishingly bad Forest Warrior (1996, starring, of course, Chuck Norris) and that the genre, with the threat ever growing, hasn't grown exponentially). For all its flotsam and getsum, and its bagginess away from action scenes, Waterworld has much to recommend it.

...We return thus, to our big question. Was Waterworld ever truly a failure? And I find myself answering...well, no. It has to be no. The film has since recouped its budget (and then some) on home release, Costner and Reynolds healed the friendship they damaged making the film, and have worked together since, and over about the last decade, the critical reception has slowly thawed from "ambitious but flawed flop" to "solid action flick". Arguably, it's both; the film's pure scale is admirable but misguided, but simply to see such impressive moments against these colossal backdrops is to excuse them, whilst its solid actioneer status comes with the caveat of its interminable breathers between. They don't make many films like Waterworld these days-its failure remains a warning-but in its odyssey of a mutated man of the drowned world leading humans home to dry land, against a fanatical leader and his henchmen who wish to usurp and spoil this last hope, Waterworld stands alone as one of the great, if curio'd, spectacles of 90s action.

Rating: Recommended

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

MY BOAT

ReplyDelete