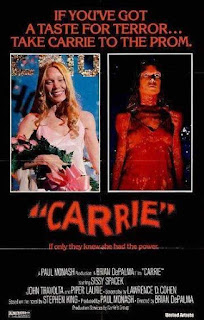

Stephen King Season: Carrie (Dir Brian De Palma, 1h 38m, 1976)

Stephen King. The very name calls to mind Jack Nicholson's manic grin, framed by a shattered door, red balloons bobbing up from sewer culverts, bloodied outcasts taking revenge at school proms, and a hundred other images from across a bibliography that counts, over the last half a century, over sixty novels, two hundred short stories, and a veritable rogue's gallery of (in)famous monsters that mark King out as the unquestionable master of modern horror and beyond, not to mention its most successful and certainly most famous figure. King's novels, thus, are a nigh unsurmountable monolith to man's inner fears, that comprise everything from otherworldly beings terrorising a community to a haunted hotel, to stories that even dare to step outside of Maine and the East Coast to tell spine-tingling tales.

The films however, are an altogether more mixed bag. For every Green Mile there is a Dark Tower, for every Christine there is a Dreamcatcher. King's oeuvre, perhaps more than any other author in fantasy or horror, is a complete crap-shoot, even without bringing King's own views on adaptions of his work to bear. It's only right, thus, in this month of ghouls, ghouls and other obligatory Halloween fare, to take a look across the length and breadth of the forty eight cinematic adaptions of Stephen King's colossal bibliography (there are over a hundred, when miniseries are counted). Welcome, dear reader to Stephen King Season, and what better place to start, than at the beginning?

Carrie's history as a novel is the thing of cinema itself; the first published novel by King, yet his fourth attempt, his early work largely short stories, its author stricken with writer's block (the first in a long and almost memetically autobiographical line of writers that make up King's protagonists), its first draft rescued from the bin and nurtured into life by King's wife Tabitha, with its success brought to the phone-less King by telegram, and its financial success launching him on his career as an author. The novel itself lays down several King tropes-his biting social commentary and nigh-obsession with the minutiae of middle-American life, his destain for religion, and the first of many zealous religious figures, and, of course, the supernatural, and children/young adults with otherworldly powers, not to mention its setting of Maine.

Enter Brian de Palma; fresh off the back of the run of the slasher movie, Sisters, the cult musical, Phantom of the Paradise and 1976's Obsession, and a rising talent alongside his peers Spielberg and Lucas, De Palma had already set himself out as a director of innovative, violent, and often psychologically driven cinema, with Obsession, even with its cuts, the first of many financial, as well as critical, successes. De Palma sets his sights upon a new target, the newly published novel by a Maine author, and, finding that nobody owned the rights, proceeded to approach United Artists, who allot him a mere $1.6 (eventually increased to $1.8) million to make it-higher than the catalogue of slasher movies like 1978's Halloween and 1974's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,but lower than the high-concept The Omen (1976) or 1975's Jaws. This low budget thus led to some sequences, most notably the extent of Carrie's rampage, being reined in from Lawrence D Cohen (the same mind behind the disastrous 1982 musical adaption, and the bloodless 2013 film version)'s otherwise faithful script.

Thus, what we get is a fairly faithful book-to-screen adaption, one that King himself, despite admitting the film's age, which certainly occasionally colours the somewhat dated special effects and music choices, enjoys. Focusing on the figure of Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) a sheltered girl who finds herself maturing into a young woman, and exhibiting increasingly unstable psychic powers we see her endure bullying by children at school, and her fundamentalist Christian mother at home. Carrie enjoys brief popularity, including becoming homecoming queen, is upstaged and mocked by the girls who bully her, and wreaks horrifying revenge, leaving a sole survivor, before a final confrontation with her mother that leaves both dead and their house destroyed, before a final, slasher-movie-esque sting, and the film's biggest single addition makes us wonder how dead our heroine really is.

Around this typical tale of revenge is a film that dives deep into the Middle American psyche, in two major sections. On the one hand is King's masterful depiction of American childhood-the film starts with the locker room in which Carrie has her first period-the film shoots Spacek as a slasher movie would shoot its victim, until the blood trickles down her leg, and the sequence turns claustrophobic, the panicked and frightened figure of Carrie (and indeed the camera, with the cinematography of Mario Tosi), hemmed in by the laughing figures of her tormenting classmates, including Nancy Allen's enjoyably nasty Chris who pelt her with tampons. With her teacher, Miss Collins, trying to comfort her, and sentencing her tormentors to a week's detention, the film nimbly pivots to King's other key theme, that of religion.

It's here, as Carrie is sent home from school to recover, that the film's true villain appears. Margaret White (Piper Laurie) is the first of a vast congregation of King's religious fanatics, but between De Palma and Laurie, she becomes arguably the best example-rivalled only by John Franklin's scenery chewing child preacher, Isaac, in the enjoyably daft Children of the Corn (1984)-and certainly its most disturbing, skin-crawling obsequiousness giving way to cruelty and violence meted out against her own child, only made creepier by her occasional moments of care and tenderness that so often act as prelude to her warped morality, not to mention the pure atmosphere of the White house, a thumbnail sketch of the religiously dogmatic That Laurie manages to turn a mere human woman into one of horror cinema's great villains is as much down to her grounded performance as it is to King's story.

From here, De Palma essentially winds the mechanism of his film for a good forty minutes, trading back and forth between Carrie's home life, where her increasing powers-perhaps where the film's budget and its age creak the most-frighten her mother into dogmatic fear of devils and fallen women and rapacious men, and the belief that her daughter is a witch, and her school life, where the plots of Chris and her boyfriend, Billy (a young John Travolta) to humiliate her rub up against that of her friend, Sue, who attempts to fix her boyfriend, Tommy up with Carrie, by way of apology to the girl. Here, certainly, we get well-wrought moments of character writing between figures, with Carrie and Tommy's friendship-cum-romance in particular seeing Carrie begin to grow in confidence, including sewing her own dress.

This, though, is not to last. The prom scene has long since entered horror cinema legend, a moment of wonderfully ratcheting tension, a montage of positively Soviet-style editing until the spell is broken with the bucket of blood cascading down over Spacek, but perhaps the sequence's genius is in its brutal economy, its red tint at once hiding and suggesting violence, Carrie, quite literally seeing red in her anger and bloodied state, bodies falling or crashing across shot, death meted out, Carrie getting her revenge on her tormentors and innocents alike. De Palma's mean streak, his cinematic viciousness, and his love for violence may be on full display here, but it is not only masterfully executed, but also, undeniably cathartic, as is the explosive death of Chris and Billy, as they attempt to run Carrie down, before the film pivots to the revenge upon her mother.

Here, the film pulls itself to perhaps its greatest moment, in which King's traditional story formula, its twisting turning sensibility is boiled down to a single scene that runs the gamut between portraying Margaret as, at turns, pathetic, bathetic, and ultimately caring for her daughter, before the film quite literally stabs the knife in and ends in a darkly, bleakly funny reverse of the film's nigh-obsession with religious imagery. One sequel-hookish jumpscare (Carrie wouldn't get a sequel till the dying months of the 90s) later, and the very first Stephen King adaption is not only a commercial success, but a critical one, its horror-thriller sensibilities catching the eye of Kael and Ebert, and seeing Laurie nominated for best supporting actress, something that the out-of-work actress would use to relaunch the second half of a career that continues to this day. It also, of course, launched De Palma into a must-have director, and, as Stephen King would soon discover, a sought after author to be adapted into blockbuster films.

But at heart, Carrie is bloody good fun, its zippy pace, its restrained budget, its reliance upon lesser known actors and economical stylistic decisions giving

it a smartly paced tension, making the film focus down onto its heroine and onto her relationship with her two persecutors, her overbearing, religiously zealous mother, brought to life in a career best performance, and the

mob of bullies at her school, both of whom eventually meet their comeuppance at her hands. It may not have the prestige, the budget, or the iconic status that some later King adaptions have, but what it proved, barely two

years after the novel was published, was not only King's status as an author, but that he, and adaptions of his films, were a sure-fire way to make a lot of money. Stephen King had arrived on the big screen, in bloody

fashion, and, through Carrie, he was just getting started.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment