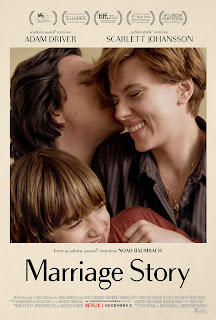

Netflix Month: Marriage Story (Dir Noah Baumbach, 2h 15m, 2019)

It cannot have escaped your attention, dear reader, that these four films I've picked out to form the first of what, undoubtedly, will be a number of Netflix-centric months hail from a band of just two years in which Netflix went from scrappy underdog arriving to crash the party, to a heavy-hitting-hit-machine, regularly scooping up a handful of nominations and occasional gongs at film festivals in the USA and beyond. Prior to 2018, though, aside from the superb Beasts of No Nation and the charming Okja, Netflix’s original films felt like, frankly, a body of work that would have steadily made its way onto the straight-to-DVD-straight-into-the-bargin-bin pipeline, from execrable western adaptions of Japanese manga (the laughably bad Death Note) to workmanlike horror, to niche documentaries on everything from the making of Andy Kaufman biopic Man on the Moon to astonishing exposes of Russian sports doping.

Here, though, a fallacy remains. The chaff, the ephemera, the dozens of films that are also-rans or worse, remain, just like the multiplexes that Netflix now threatens to supplant. For every Roma, there are a dozen naff romcoms, for every The Irishman there are rote action adventure films, or clunky dramas, and for every Uncut Gems, there is, inevitably, a Marriage Story. For every wildly inventive intoxicating cinematic experience, unbound by run-time, and quite honestly, by the need to make a profit, there's a painfully by-the-book film that trots out every Allen-esque cliche about being a creative person in an empty, loveless relationship with another creative person, whilst clambering through every creative stereotype LA can muster. Amongst this cinematic malaise, our protagonists, Adam Driver's Charlie, a theatre director, and Scarlet Johansson's Nicole, an actress, navigate their messy divorce and every obvious dramatic turn and hackneyed moment of quasi-emotional resonance that this brings.

For Marriage Story, despite its star-studded cast, including Ray Liota and Laura Dern, who won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress, for her role as Nicole's waspish and quick-witted lawyer, is a strangely underwhelming affair, a film that, but for a final forty-five minutes that finally seems to nail the emotional weight crushing down on both Nicole and Charlie, is a strangely self-important film. It's a film about fantastically successful Hollywood creatives struggling with the creative process and with the breakup of their relationship, and its central conceit, in blunt honesty, is Noah Baumbach role-playing via Driver through his own messy divorce with Jennifer Jason Leigh. It's the sort of "write what you know" shit you'd expect from a first time screenwriter, not a man who's written two of the best Wes Anderson films and been nominated for two Academy Awards, one stunningly enough for this turgid mess.

We're led, in what feels like Drama Screenwriting 101 through a boring, mumbly mess of a film somehow starring four of my favourite actors (the great Wallace Shawn appears, inconceivably for an actor of his talents as an oddly horny New Yorker stereotype), whilst a quadaluded Randy Newman plonks along, and Driver and Johansson exchange pleasantaries, screaming matches and court dates in with all the grace and depth of a TV movie, whilst scenes that may be deliberately or unintentionally comedic flit past the window. Both of them are looking for purpose, for motivation, for anything that raises their character above what amounts to an authorial self-insert and a hatchet job on his ex-wife, ratting around in a film, where the hawkish, predatory lawyers that intrude upon this family drama, and the likeable child at the centre of it all, are the best thing about it.

We begin with the duo in counselling, and even at this early point, despite the well shot vignettes of their shared life, as each partner reveals their thoughts upon the other, there's a colossal flaw in this film, with how Baumbach writes dialogue and how he directs it. This is a film studded with excellent individual performances. Driver storms through the film a frustrated creative, who only seems to relax around his troupe of actors, we see Johansson steel up, her changing appearances throughout the film seeing her slowly drift away from the muse to her ex-husband, and in each of their corner, we have sublimely nasty performances from Ray Liota as Charlie's lawyer, and pitted against him, Laura Dern pulls off a career best performance as this figure of intense power and malignity in feminine guise, enjoying every twist of the blade against Charlie's case.

There are great moments of to-camera quasi-silloquay-one of the film's most affecting shots is Nicole pouring out her heart to an off-screen Nora, shot in almost uncomfortably vulnerable close-up, whilst Driver is given long, drifting moments of isolation in his hotel room once the separation goes through. But put these actors in the same room as each other, particularly as Nicole and Nora "force" Charlie's hand into getting a lawyer, in the form of the gentle, but painfully naive Bert (Alan Alda), or the clumsy courtroom scenes in which Liota and Dern get to flex, for a fleeting moment their acting muscle, and it becomes a bizarre mess of a film, in which four to five of the best actors in cinema seem to be delivering their oh-so-clever or mumble-core level lines in abstraction, at, rather than to each other.

The first meeting between lawyers borders, in particular, on the laughable, so leaden, so on the nose, so clunky and overwritten, whilst at the same time trying to capture the verité and deadpan lightness of Baumbach's partner in crime, Wes Anderson, that it becomes laughable. For an Oscar-winning performance, it is Dern that gets a large number of the worst clunkers throughout, particularly in her scenes with Nicole/Johansson as though Baumbach has never actually heard women speak to each other, throwing in everything from references from the Virgin Mary to almost cartoonish misandry. That she makes this character anything but a two dimension monster, though one that the film largely vanquishes seemingly by mistake, is a testament to Dern's qualities as an actress.

Even Driver and Johansson are not immune to this. Nicole and Charlie are likeable figures, and the fact that the last third of this film, carried by their performance alongside the excellent child actor Azhy Robertson, as their son, Henry, basically saves the film from being irredeemable, both of them are frankly boring, badly written character. Henry, for his part, is the sole consistently good actor in this, a quirky, well-written, precocious and frankly human character in this otherwise avatar-strewn mess of a film. Up until Charlie explodes at his now ex-wife, screaming and punching walls, before memetically breaking down, an action that finally pushes them from being detached Hollywood cyphers, self-inserts for Noah Baumbach to retell his divorce and give it a happier ending, to flesh and blood fallible people, they have drifted through this film, their marriage and themselves innocent martyrs of the parasitic divorce industry, their separation, on their own terms almost hopelessly naively optimistic.

It, unlike Baumbach's other major work, 2005's The Squid and the Whale, which also draws upon his experiences of his parents' divorce, has no in for the audience, its duo of overly precious theatrical types, hamstrung by their lives being built on their creative rather than romantic partnership. It nails this malaise, this realisation that Driver's character has essentially run roughshod over his wife's desires, but this autobiographical slip on Noah's part is a scab he's unwilling to pick, and we see, for a theatre director that somehow gets a play as pretentious as the film that surrounds it, a Hollywood idea of experimental and modern theatre, to Broadway, go from triumph to triumph. In frank terms, the divorce is more a means to an end, its ending throwing both of them to even greater heights of creativity.

It's a tiresome mess, a self-aggrandising, self-celebratory bit of wish-fulfilment, Driver Baumbach's bewildered wide-eyed creative self-insert, bumbling, faultless and guileless into the

trap set by his wife and her manipulative lawyer, she and Liota's other vulture swirling around their collapsing marriage to pick its carcass clean, to tear chunks off each other, regardless of the cost to their son and,

indeed, their friendship. It's the sort of schedule-padding directionless mush, that, but for its sudden moment of catharsis, its explosion of actual emotion in its most ridiculously overblown moment, and its patronage

by Netflix to gift it a cast of far higher quality that it honestly deserves, would be a so-so drama on a wet Sunday evening.

But more than this, it, and this season as a whole have indicated the double-edged nature

of Netflix as a platform. It, undoubtedly, gives other cinematic voices a space, and films that the traditional studio system would balk at for the size of its audience on the size of their budgets a chance to succeed, unhindered

by the need to turn a profit. But with this democracy, comes the question of quality control, of being able to pick the good films from the four hundred plus films released a year via the platform. Never has the critic been more important, in signposting the way to the best this and other platforms offer, and away from films like this

sorry, self-important mumbling mess.

Rating: Neutral

Like articles like this? Want them up to a week early? Why not support me on my Patreon from just £1/$1.20 a month! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment