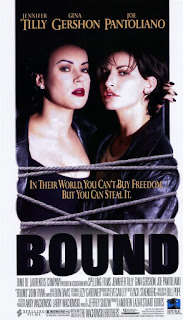

Romance Season: Bound (Dir The Wachowskis, 1h 48, 1996)

It's something of a disappointment that Bound stands largely alone in its genre. Too often queer depictions in cinema is a genre tethered to romance, to drama, to

the endless rotation of coming-of-age-and-coming-out films of various stripes and dealing with unrequited or past loves, of which a scant number seem to be directed by queer directors, and a fewer still seem to step outside

these scant guidelines. Yes, there are crime thriller films like Set it off (1996) or the excellent The Handmaiden(2016) and The Favourite (2018) that use lesbian relationships between classes to explore female power and relationships, and 2015's Kiss Me Kill Me's neo-noir depiction of a gay man dealing with the murder of his boyfriend. There are, though few films in the mainstream cinematic canon-save perhaps for Lumet's Dog Day Afternoon (1972) that manage to make their depiction of LGBTQ+ life a natural, matter-of-fact element of their story like Bound does.

Depicting the growing relationship between the independent and unapologetically out Corky, (Gina Gershon) and the closeted and connected to the mob, Violet, (Jennifer Tilly),

Bound could have simply been a film about this relationship, but, by expertly melding this onto a neo-noirish tale of missing money, the Chicago Mafia, and

the spiralling chaos that explodes once Violet's partner, the volatile Caesar (a brilliantly nasty performance by Joe Pantoliano) takes matters into his own hands. What we're left with is a film that matches a gritty,

violent low budget crime film (just $6 million), with an unapologetically lesbian pair of heroines, whose romance is skilfully interwoven into the plot, but depiction never stoops to stereotype, but above all, are given the

same pathos and agency as any male hero.

Beginning with the introduction of Corky in media res, quite literally bound, the film flashes back to the first meeting of Corky, Violet and Caesar in the elevator, before all three of them are expanded

upon, from Corky's ex-con status, and her appearance at a lesbian bar, to Violet and Caesar's relationship, and Caesar's brutal beating of the hapless Shelly, in the first of the film's many superb match cuts.

Violet and Corky strike up a relationship that quickly becomes physical; to the film's utter credit, whilst the two love scenes are shot sensually, unlike other films of this genre, it never feels exploitative, or created

simply to titillate a heterosexual male audience. It is, without a doubt, integral to the film's plot-to remove it, to cut it down, is to suggest that our heroines sexuality is somehow

taboo, or not worth giving the same weighting as a heterosexual scene serving the same narrative purpose.

The duo begin to hatch a plan, using the location of the cash with Caesar, after the brutal offing of Shelly

leaves it bloodied and in need of quite literal laundering, as a chance to get their hands on it. In perhaps the most stylish sequence of the film, and one you can't help wondering if

Stephen Soderbergh lifted it for his remake of Oceans 11, we get the prior explanation of the plan alongside the plan taking place. Caesar, unfortunately, scuppers part of it, his already

volatile performance ticking up a notch as he begins to blame his rival Johnnie, rather than simply making a run for it. Enter Gino (Richard C. Sarafian), the local mob boss, Johnnie (Christopher Meloni), and Gino's bodyguard,

and here the tension is perfectly ratcheted up with Corky waiting, for the first time in the film, passive, as Caesar executes the trio after revealling, in his eyes, Johnnie's treachery.

From here, the film,

if anything, becomes more claustrophobic, as Caesar tries to hide the bodies, and both the police and another member of the mafia, Mickey (John Ryan) make appearances-there's more than a touch of Reservoir Dogs, to which several critics, rather swayed by the violence and slow unravelling of hard and neurotic men, rather unfairly compared it, in the almost stage-like sense of this final third

of the film, as the film tightens up, Caesar becoming increasingly trapped and neurotic towards our heroines, reaching a crescendo violence, in which the relationship between Corky and Violet finally reaches its payoff in

an excellent, and perfectly noir-ish ending.

Bound's strength, undoubtedly, lies in its characters. The film wastes no time in quickly establishing both of its heroines-Corky

is a butch ex-con, unapologetically lesbian-down to the labrys tattoo on her shoulder that, for a duo of directors that have always dispensed with convoluted symbolism, together with the rest of her ink marks her out as tough

and independent. Violet, on the other hand is a woman essentially trapped by her connections to the mob, by her volatile partner, by, as the Wachowskis' put it, the "boxes of our lives", whether that be the closet,

the entrapment of the life of a housewife, or, indeed, in servitude as a painter and decorator, because no-one else will employ you. This is perfectly encapsulated by the claustrophobic sense of the film, with it taking place

almost entirely inside, and even then in just two rooms and a corridor, the budgetary restraints adding to, not detracting from, the film's key theme

Yet, Violet is arguably the one with the most agency in the

film-it is, after all, her that seduces Corky, it is her that, understandably, weaponises her femininity into a facade of a helpless woman to the mob, not just seen, but heard as her voice pitches up into the girly voice of

a gangster's moll, a facade she only feels she can drop, together with the hyper-feminised appearance, around Corky. It is she who brings Caesar's plans crashing down, through the film's final taut scenes, as she

plays along with, and then finally stands up to Caesar's belittling and violence, and it is she who rescues Corky and defends her against her former partner. Her character is anything but the damsel in distress even

a butch/femme reading of the film could suggest, let alone a heterosexual reading, and to see Tilly drop the facade of the helpless passive moll entirely by its end to something less vulnerable but clearly still feminine is

frankly some of the best character writing the Wachowskis have ever done.

It is in the film's pacing, though, that its true master-stroke is. The film, in short, does something very smart with their relationship-whilst

it's something used against the film from certain sections of its audience, by placing much of its romance, the formation of their relationship at the start of the film, it becomes a film

of a couple pulling off a heist together against one of their former employees. That this happens to be a lesbian couple swindling a neurotic violent mobster who Violet was formerly in a relationship with is so matter of fact

it's both audacious and remarkably refreshing. That this romance and relationship is believable, that it is two flawed and human and treated with respect, rather than being merely objectified or sexualised feels like nothing short of a triumph.

Bound, thus, still feels remarkably fresh, an intelligently made low-budget film that perfectly marries a strong, well written lesbian romance with the bread and butter of a crime thriller without

paying a disservice to either half of its concept. What results is a superbly taut, unapologetically queer mainstream film in which our queer heroines are every inch the capable heroes, the film nimbly front-loading its romance

so that Corky and Violet are an established couple, a fully formed duo rather than put through the tired paces of the closeted LGBT protagonist in their search for love. That Bound stands almost alone in its genre is not just disappointing, but a grave flaw to mainstream cinema that it so rarely manages to tell queer stories outside a very narrow sliver in a select few

sub-genres.

Rating: Highly Recommended.

Comments

Post a Comment