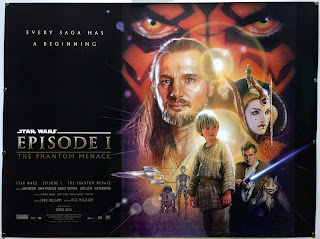

Prequel Month: Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (Dir George Lucas, 2h 16m, 1999)

No cinematic trilogy, in the fifteen years since its final instalment has received the degree of critical claim, mauling, exoneration, and reappraisal of the Star Wars prequels. An origin story

for its greatest villain, the Sith Lord Darth Vader, taking him from child slave Anakin Skywalker to leader to fallen hero, it is a trilogy of messy, inconsistent, poorly acted and overly effects laden films that fail to even

reach, let alone challenge the majesty, or indeed the charm of the original trilogy. Yet, it is a curious trilogy, a trio of films that show startlingly original concepts in places, create new and expand upon existing characters,

and unquestionably changed mainstream cinema's trajectory in its triumphs and failures, not to mention a singular vision of one of cinema's greatest creators.

Twenty-one years after the first film, Episodes I, II and III have received a curious afterlife, as fans and critics alike pore over this cinematic wreckage, either doubling down upon the talking points

that hang round this film like so many albatrosses, or reappraising this as a underrated, if flawed epic, a yardstick against which Disney's own uneven trilogy, where workmanlike fan-service cinema sandwich a gonzo and

utterly divisive vision of post-Lucas Star Wars is measured. This, together with its support through its beloved status across the internet, from internet memes to full-on attempts to re-edit and redeem the prequels, to its

continuation in the form of the critically lauded The Clone Wars television series has only lengthened the shadow of the prequels.

Nowhere is this shadow longer than in the first

of the three films, The Phantom Menace. Its siblings may be, respectively, a dull film spectacularly hamstrung by some of the worst romance ever put to film (Attack of the Clones) and a last-gasp attempt to re-capture the magic of the original trilogy in a film utterly stolen by its strong central trio of Palpatine, Skywalker and Kenobi, but the subject

of so many think-pieces, so much mental ammunition, so much hate and love, the bullseye of the trilogy is, unquestionably, Phantom Menace. Over twenty years on, it is daubed as a betrayal, a film made by a person spectacularly out of touch with film making, a crushing disappointment that coloured the other two films, destroyed

the careers and lives of two of its central cast, a film so overladen with hype and merchandising that it utterly overhangs any quality that the film may once have had.

This, however, is twenty years of bitterness,

hindsight and bullshit. Hell, I was there in the dying months of the millennium as the hype machine rolled into town, bringing with it a colossal vanguard of merchandise, from Lego sets i treasured as a child-some of the first

toys I can remember-to a cavalcade of action figures, to the more questionable, of which a great degree was, of course, Jar Jar Binks-themed. I remember distinctly the palpable excitement, the sense that, really, has only

been recaptured once, with the release of The Force Awakens, which, unlike Phantom Menace, at least in hindsight lived up to it. It's certainly one of

the first films I can remember seeing in the cinema, along with my younger brother and (still) politely baffled father, a man who still vividly remembers Jar-Jar Binks.

We were caught up in the hype, perhaps, in

the capitalist machinery that Lucas practically perfected with the original trilogy, but I can vividly remember the excitement of my peers, the recreation of lightsaber fights, and the other key points of the film, in the

playground. We loved, perhaps devoid of the critical faculties that better films and age would grant us, this explosion of battles and pod-racing and starfighters and the funny alien who made flatulence jokes, this film. It's

at this point I must make an admission. For all my love for Star Wars, on big and small screens, and in its myriad merchandise and publications, it's been a full decade since I saw any

of the prequels in anything other than suitably memetic clips.

It's thus...surprising that I don't hate Phantom Menace. It is, undoubtedly, a fundamentally flawed piece of cinema, from its in-essentiality in the entire Star Wars saga, such that several watching guides (including the infamous Machete Order) entirely dump the film to the wayside, with few, if any plot threads carrying through to the second and third

films, to its wooden acting from certain cast members, to the film's rather questionable relationship with minorities. Episode I, is, unquestionably, even from the point of view of dumb white kids in the late 1990s to

early 2000s, stuffed with racial stereotypes.

It's fair to consider that, yes, the original trilogy has its own problem with race-Lando, seemingly the only black man in the entire galaxy, for all his style

and eventual allying with the Rebellion, sells our heroes out and only joins once he himself is betrayed, whilst Afro-American critics and commentators have debated the black-clad, Afro-American voiced, Darth Vader's relationship

with race for years, even being lampooned by uber geek Kevin Smith in Chasing Amy. These, though, are nothing compared to the colossal failing-a failing that, decades before the "SJW

agenda" of the (far more representative) sequel trilogy, was a major part of contemporary reviews, and has only become more apparent in hindsight.

This problem is apparent from the very opening of the film-the

Trade Federation are cowardly, creepy, and unmistakably Asian-coded, a group of far-East voiced duplicitous figures who exist via group-think and are easily manipulated into action by Darth Sidious. Watto, the junk trader

who owns Anakin and his mother, is equally stereotypical, a gambler, a slave-owner, and equally transparently Arab-coded, a hookah-smoking grizzled figure for whom money and nothing else talks. It's frankly painful, especially

for a universe whose existence owes so much to Asian and Arabic culture, and whose popularity is huge in both diaspora, to see this-even at the time, I can remember being...strangely disconcerted by these figures, especially

in a universe that had always previously painted the human-and Nazi-coded Empire as the source of villainy.

And then there is Jar-Jar. There are few figures in modern cinema who have received the hate, the cruelty,

the venom that Ahmed Best has carried for the past two decades, and though Jar-Jar and Best himself have finally come in from the cold in the last few years, culminating in his hero's welcome at last year's Star Wars

Celebration, this role practically destroyed Best, an ominous prelude to the hate aimed at John Boyega, Kelly Marie Tran and even Daisy Ridley in recent years, and his return to a universe that previously shunned him speaks

more of his quality as a man than any change in the Star Wars fandom.

Yet, it cannot be said that Jar-Jar the character is faultless-the Gungans that Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) and Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor)

find themselves requesting aid from, and later, together with Queen Amidala (Natalie Portman) allying with, are unquestionably Jamaican/Caribbean coded, their dialogue a shoddy and offensive co-opting of the patoise of this

region into an unintelligible and questionably comic joke of a language, a race of quasi-dread-locked primitives whose most notable representative is a bumbling fool-archetype, who stumbles, bluffs and klutzes his way through

the entire film, relying on his Jedi protectors to save his neck, all the while making poop and other toilet humour jokes.

Best's Jar-Jar is the canary in the Phantom Menace coal-mine. He's certainly the most glaring example of Lucas's poor direction, and poor writing, together with the oft-and rightfully-lambasted midichlorians, a detail long since

left in the dust of Star Wars' universe, but there are the stirrings of the problems that would strike to the core of Attack of the Clones. Portman and her retinue are oddly wooden, except when she takes the mantle of Padmé, the beginnings of the relationship that will bloom between Skywalker and Amidala clunky

despite both Portman and the unfairly lambasted Jake Lloyd's efforts, the sweetness of what should have been the first meeting between the Galaxy's greatest love story utterly lost in terrible metaphors and poor direction.

This clunkiness does, at points, rear its head in the plot-the political drama, whilst giving the film a suitable heft, and certainly, from an adult sensibility, a slightly jaded idea of the Republic only previously

regarded as a golden age in the Original Trilogy, is utterly out of place and overcomplicates what is already a complex tale, bogging it down in minute after minute of political wrangling and Senate scenes. The film is also

overly keen on its fanservice-throwing in needless cameos of bit-part players, Expanded Universe heroes, and in a role that goes nowhere, Anthony Daniels' C-3PO as Anakin's creation. But perhaps, most gallingly, it

feels...inessential. There is nothing important, apart from a pint-sized Anakin meeting his mentor, Obi-Wan and his eventual wife, Padmé, in this film.

It does not need to exist. It wraps every single thread

up, aside from the existence of Sidious, in itself, a self-contained film that practically stands alone. One can well imagine, in a parallel universe where Lucas kept his cinematic chops honed in the nearly twenty year gap

between 1977 and 1994 when he began writing Episode 1, a tighter story with an older, more experienced Anakin alongside Obi-Wan, and the beginning of the dark path he will head down as he eventually succumbs to the Dark Side

of the Force. It's a great what-if. What it is, though, is a story where its supposed hero is sidelined to bit-player, where everything feels, in a word, unnecessary. That this is the new opening, the unquestionable starting

point, of one of cinema's great epics (despite watch order deliberation), only worsens this sensation of a false start, a needless preamble before the great narrative heft of Episodes II and III.

Yet, there

are, without a doubt, good things about Phantom Menace. The use of CGI, whilst increasingly embellishing the Original Trilogy to the point of cinematic revisionism,

and a pale imitation of this trilogy in its grounded physicality, gives Phantom Menace a sense of grandeur and scale, especially on the planet-sized city of Coruscant, and on the Italio-Venetian

world of Naboo, a scale that is seen elsewhere in the battles, both in space and on Naboo, as the finale rumbles into a suitably colossal final third, as its four action set-pieces intercut. Its set-pieces, are, certainly,

where Phantom Menace excels best, from the suitably tense pod-racing scene, where the speed and chaos of motor-racing is given a suitably science-fiction angle as pod-racers collide, rivals

fight, and where the film's digital effects work is at its best, to the four-way battle of Naboo, from ground battle to infiltration of the Trade Federation-taken palace to space battle to lightsaber duel are given suitable

momentum, and where, unlike much of the rest of the trilogy, each conflict plays its part.

At the centre of this all, unquestionably, is the film's true central trio, Jinn, Kenobi and Maul. Maul, certainly is

this film's outstanding figure, a nigh-silent menacing figure, his lurid face tattoos making him both iconic and terrifying, the clipped tones of British comedian and actor Peter Serafinowicz (probably otherwise best known

as the housemate in Zom-Rom-Com Shaun of the Dead and "a-hole" dubbing Garthan Saal in Guardians of the Galaxy) dubbing Maul as a man of few, precise, and chilling words. Yet, it is Ray Park that gives Maul his danger, his physicality, his driven and dangerous and almost feral fighting

style, and it is his iconic dual-ended lightsaber, oft-homaged but never improved, that stalk through this film, disguising his tantalisingly short appearance on screen (a brutally economic six minutes). Maul's popularity,

of course, has led to an impressive afterlife for the Sith Lord in Star Wars' animated outings, but without his initial impact, none of this would have ever left the drawing board.

It is in the figures of Qui-Gon

and Obi-Wan, though, that the true heart of the film is found. McGregor, for his part, is a young and impetuous type-the subversion of the kindly Ben Kenobi into a tough, impulsive young warrior who supports his master's

decisions, and acts as his eyes and ears aboard ship whilst our protagonists are marooned upon Tattoine, and whose skill as a warrior and a Jedi are neatly juxtaposed with his slightly naive and dismissive view of both Jar-Jar

and Anakin. Yet, it is he who defeats Maul, who agrees to become Anakin's master, whose relationship with the boy will expand and grow nuance as the trilogy builds, inevitably to their final confrontation in Revenge of the Sith.

Yet, Neeson, simply put, threatens to walk away with this film, and his absence, compared to his adversary, in the larger Star Wars canon, especially in the light of

the equally outspoken and equally nuanced Rey, a figure who equally treads the middle ground between light and darkness, is a strange and faintly disappointing thing. There is a warmth to Neeson, a sense, compared to those

other Jedi Masters the franchise subsequently introduced that rivals Frank Oz's Yoda, of a person in tune with the universe, a sense of the more mystical and Zen-coded elements of the Force. Moreover, his is a portrait

of a more nuanced form of the force than the obliquely black-and-white of the original trilogy, a man who pushes the rules aside in a quest for the greater good, no matter if it goes against the rigidity of the Jedi code that

will eventually doom the order to the brink of extinction

Watching Qui-Gon now, in the aftermath of The Last Jedi's version of Luke Skywalker, there is unquestionably an echo,

a sense of the long-dead Jinn echoing down the years, into a grizzled Master who now sees the flaws of the Jedi, the innate colourlessness of the Force, a figure who stands outside this simple light and dark sensibility. It

is he who drives the film forward, his decision to wager everything upon Anakin, to trust in the boy and his ability, his support for the Queen Amidala's decision and his belief in her plan, even as it threatens to fall

apart. Few figures in the Prequel Trilogy step fully formed onto the screen, fewer still have not been mined over the two decades of canonic expansion and fandom exploration, and yet Qui-Gon remains, a towering figure whose

death ripples across the Prequels and beyond, an enigma.

Whither The Phantom Menace? It's easy to consider it a failure, easier still to rush to its rescue, to uphold the centre-piece

of a childhood of Lego and action figures and Darth Maul masks and sweets. Perhaps the thing one gains most from twenty-one years hindsight, a period in which the Prequels have become arguably western sci-fi's biggest

and hottest potato, endlessly juggled about between its supporter and detractors, is that The Phantom Menace is flawed. It could never reach the heady heights of the Original Trilogy. It has

to begin with a young Anakin, before he became Vader, it always had to be. Lucas, absolutely, misstepped with how young Anakin was, overcomplicated the plot, threw adult fears like taxation and government corruption and trade

disputes into a story that has and will remain teen escapism.

It is flawed, a film that leans heavily on lazy stereotypes of the very people who made Star Wars what it is, a ethnographically rich adventure taking

influence from myriad Arab and Asian cultures, a film that destroyed the lives of two of its heroes, one of whom still remains damaged by a fandom that continues to be petty, divisive and cruel. It is flawed, and messy, and

yet. And yet, for all its cracks and breaks and mess, for all its unnecessary existence, for the two decades plus of think pieces, of tear downs and posthumous plaudits and the entire books worth of material on how this destroyed

or made childhoods, for all its iconic lightsaber fights, for all the metric tonnes of Darth Maul action figures and Jar-Jar Binks rubber tongued toys and countless childhoods marked by this ephemera, for all the hype, for

all the tidal wave of merchandise, for all these years, The Phantom Menace endures. Always.

Rating: Recommended

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment