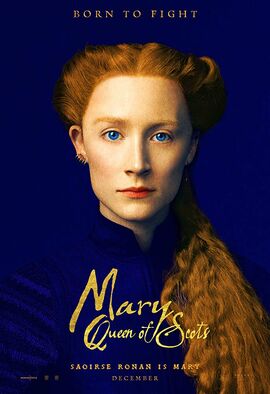

Mary, Queen of Scots (Dir. Josie Rourke, 2h 5m)

Directorial debuts are a strange beast, either small scale versions or a more embryonic, less surefooted, or even radically different style. For her cinematic directorial debut, Josie Rourke, already a veteran of the stage, certainly begins her career on screen well. In her depiction of the life of parallel queens Mary, Queen of Scots, and Elizabeth I of England, she compares, in a painterly and poised picture, that occasionally belies her theatre origins, the feminine, passionate Mary-Saorise Ronan, in what, even for an already illustrious career may be her most commanding performance to date, and the childless Elizabeth-Margot Robbie, who rules kinglike, married only to her throne, in a visually striking and excellently wrought film.

Ronan, in a word, rules this film, in the same way she rules Scotland, and the imagination and fears of Elizabeth, in a performance that shows Mary as a confident, commanding queen, expertly manoeuvring the masculine world of power, but never losing her femininity-indeed, there is a sensuality to her performance that, in a month that sees two films considering and exploring female queens wielding power in male dominated periods, draws her apart from Robbie's Elizabeth, and indeed from many previous depictions of Mary that tend to focus upon her later years in England. Indeed, Mary's power is in, unlike Elizabeth, her youth, and her ability to bear an heir, something that haunts Elizabeth in two scenes involving a foal and its mother, as though even nature itself mocks the English queen for her inability to produce an heir.

Moreover, in the very appearance of Mary against Elizabeth, in the naturalistic makeup and long flowing hair, against the heavily made up and bewigged Elizabeth-something particularly stark in their climatic meeting in a barn, the scene that comes closest to being pure stagecraft, as layers, both physical and emotional, are stripped away, and they finally come face-to-face, before Elizabeth strips further layers away of her own appearance to show, in stark terms, the divide between them. Yet, as Elizabeth herself states, it is Mary's youth, her femininity and her ability to produce an heir, that proves to be her downfall. Ronan imbues Mary as impulsive, rash, and in the continuing friendship with Italian minstrel David Rizzio, which ends with his brutal murder, even foolish, causing friction, with her remarriage, after the death of her second husband, Lord Darnley, who finds himself caught in a web of counter despite her Catholic faith, to her chief general, the Earl of Bothwell, which eventually, at the hands of her half brother, and protestant preacher, John Knox (a sterling fire and brimstone performance by David Tennant), to her downfall, and exile in England.

Elizabeth, in comparison, is a woman in a sense, married to the throne, and suspicious of any who try to foist a husband on her, for fear of her power ebbing away-hers is thus a reign alone, without husband or heir, and at several points, Robbie imbues Elizabeth as almost neurotic, trapped by duty to the country, paranoid at losing power in marriage, and haunted, as age robs her of the ability to produce an heir by Mary's ability to do all three whilst still remaining powerful and in control of her own kingdom. This boils over in the aftermath of her smallpox, as she storms into a fencing session, and breaks down in front of Dudley, her lover. This is perhaps the only moment we truly see the mask-and by the end of the film, it truly is a mask, almost shockingly, artificially white-slip, the one moment we see the woman in the Queen, rather than the man she forces herself to be and by the end of the film, Elizabeth is, visually and otherwise, stripped of any femininity she has.

Thus, at the centre of the film, ruled by two dominant performances by two female actresses at the height of their powers, the film considers female power, and indeed how this wielding of female power is influenced, and made more powerful by the female ability to produce an heir, and weakened by the inability to produce one-Elizabeth, being unable to produce an heir strips herself of femininity, describes herself as a man, and by the end of the film, is almost a mockery of femininity, a woman hiding behind a mask as she steels herself against her own gender, a mask that only cracks at the point she meets Mary, the opposite of herself, a strong, feminine woman who has both husband and heir, and the crux of the film is the struggle between these two poles.

Rourke's theatre background, aside from the excellent dialogues that intersperse through the film, leading to the final showdown between Mary and Elizabeth, can be seen in the way that shots are framed, and often held on for long periods of time-the first meeting between Lord Darnley and Mary is kept as a locked-off shot into which people step in and out of, whilst there are a number of excellent closeups. There is, however, a painterly ability to the entire film, with beautifully framed shots throughout the film, including many where the action in Scotland is matched or contrasted, including overlap of diegetic sound between location, with that in England, and vice versa. Whilst there are a couple of moments that, should Rourke have presented this as a play, may have been better than they appear in the film, but are so minor in this case that they never distract from the film in general.

Mary Queen of Scots is thus a excellent, visually exquisite portrait of a strong, powerful woman, whose sex and power eventually led to her downfall, against a strong woman who in essence stripped away her own gender in order to rule. If this is how Rourke begins her career in cinema, she will certainly be a talent to watch.

Rating: Highly Recommended

Comments

Post a Comment