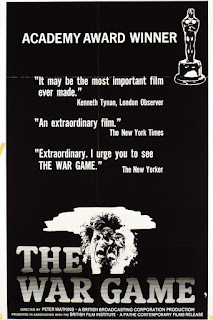

Under the Mushroom Cloud: The War Game (Dir Peter Watkins, 44m, 1966)

Cinema in the aftermath of nuclear war tends to flinch. It's easy, as many films do, to jump ahead a few decades, to sanitise the collapse of society and the immediate effect of nuclear bombs falling on

suburbia, and the death, destruction, illness and societal collapse that follows. They also, unlike the films we've spoken before, tend to have a single preserve-the 1980s. Testament (1983), The Day After (1983), Threads (1984), Barefoot Gen 2(1986) and When the Wind Blows (1986), are resolutely accurate depictions of the aftermath of nuclear war, and all owe a debt of influence to one film.

Finally released in 1985, some nineteen years after its production and limited cinematic release, with a Best Documentary Oscar under its belt, came The War Game, an unflinching verité look at the impact of nuclear war on the United Kingdom, and whose infamous shelving by the BBC must be matched with its influence and the long shadow it

cast across films about nuclear war-and war in general-to this day.

Peter Watkins is one of the great unsung directors of British cinema; even in his eighties, he still makes provocative and staunchly political

films, often re-enacting events in front of camera, often casting amateur or local actors, or evoking news or television coverage, whilst exploring everything from the Paris Commune of the 1870s to the life of Strindberg to

Edvard Munch and the stresses of everyday life in Denmark and its high suicide rate. Most of all his work meditates upon a healthy distrust for the mainstream media, and a strong anti-war, and in particularly anti-nuclear

war, stance. These are seen everywhere in his filmography, from Gladiators (1969), which frames war with sporting TV coverage, to Resan (The Journey, 1987), the second longest non-experimental film ever made which focuses on nuclear weapons and defence spending,

to his fictional narrative films The Trap (1975) and Evening Land (1977)

All of these act as successors to The War Game, a film he made when he was barely 30, as part of the groundbreaking The Wednesday Play series (which also featured Cathy Come Home and Up the Junction). The War Game begins by laying out its first stark message. The film focuses on the South-East

coast of England, in particular Kent, (where much of the film was shot on location, largely involving locals, as typical for Watkins' production), also home to many of the airfields from which the Vulcan and Victor bombers

that would drop nuclear bombs on enemy nations would take off.; this, and the presence of major cities, make the South-East the epicentre of nuclear attacks. From the UK, the lens widens, with looming, and entirely dramatised

war between Chinese and American forces seeing the Americans threaten nuclear attack, to which the Russians threaten to invade Berlin.

laced onto a war footing, the "documentary" crew follow the action,

as local governments are forced to, and struggle to, deal with the sudden evacuation of large chunks of the population, and compulsory rationing, both harking back, in grimly shot sequences, to the Second World War. There

is to be no recreation of the Blitz spirit here. With Michael Aspel's narration, even before the bombs drop, there are indications, both on screen and from the narration that even these evacuation attempts are likely

to fail,undermined by the unwillingness of wives to leave their husbands, and homeowners to billet evacuees. Against this, the film depicts the complacency of the British public, the vox pop interviewees clueless about the

effects of nuclear bombs, the impact of even a non-nuclear war on the British public, and, through the figure of a gun-toting, and almost sinisterly over-equipped resident, whose property is dotted with refuges.

Bleakly

juxtaposing this, as Aspel informs the viewer that most families will have mere minutes to react to the launching of nuclear bombs, with the incompetence, and ill-preparedness of the UK. This manifests in several ways across

the pre-strike segment of the film, dominated by profit, and profiteering, with the guidance rushed out to families, having previously only been available for purchase, and the government unable, or unwilling to finance the

materials to allow people to build suitable shelters. Following a doctor as he makes his rounds, it is here, in brutal, and remarkably visually simplistic terms that the film depicts the nuclear attack, the panic of the siren

giving way to the mad scramble for the household the doctor is visiting as they attempt to barricade the windows from the worst of the blast. The camera, verité, follows one of the doctor's assistants outside, to

find one of the family's children, and a -flash- of white briefly covers the screen.

The bomb has dropped, blinding the worker and the young man, and igniting the furniture inside, the panicked family terribly

ill-prepared for the bomb, and its power. The scene changes, to, in even more visceral terms, depict the blinding of a young child by the incredibly intense light of the nuclear explosion, and the equally chaotic and tightly

shot scene that follows depicts the blast front as chaotic and frightening. Worse, and more graphic is to come, with the firestorms' destructive power on full display as firefighters are helpless to stop them, but their

even-more deadly side shown, as they and civilians are overcome by the heat and lack of oxygen, the camera impassive as they fall, the savage indiscrimination of the bomb on full display. The retaliation by British forces

is almost horrifyingly matter of fact, and the juxtaposition of the interviewees, largely keen to see their nation counter-attack, against the chaos-Aspel comments that up to half of the population could be killed by the opening

salvo of a nuclear war-is even more so.

It is here, undeniably, that the film's darker, and most uncomfortable moments begin. Watkins' research based the aftermath largely on Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the

bombing of Tokyo, Dresden, and Hamburg, buildings razed to the ground to deal with irridated bodies, there being simply being too many to bury. Elsewhere, in one of the starkest scenes, in which the film comes uncomfortably

close to footage of the worst horrors of the Second World War in its matter-of-factness, as those too ill for medical assistance-Aspel starkly informs us that every surviving doctor will be responsible for up to 300 patients-are

put out of their misery by police and military. Here, superbly acted by the amateur cast, we also begin to see the mental effect on the survivors.

From here, things only deteriorate, society breaking down into chaos,

till the country resembles a police state, with soldiers executing anyone who goes against the increasingly draconian laws of post nuclear England, whilst the survivors are either ailing, or living hollow existences, the film

depicting in bleak terms the first Christmas post the nuclear war, and the desperate conditions that the orphans of war live in. It is thus, hardly surprising, that the film ran afoul of the BBC's board, the film dubbed

"too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting", with Director-General Hugh Carleton Greene concerned that its power to shock and offend would also affect the depressed,

the elderly and the lonely, with fears of mass suicides or popular uprising chief on the minds of the BBC's highest figures. Whilst it seems a hopelessly beneficent act, a coddling of audiences by "Auntie", behind

the scenes things were far more politicised, with Oliver Whitley, Greene's assistant, suggesting broadcast "come hell or high water"

It has long been suggested-and nigh proved-that this pressure came

from either higher, from the Harold Wilson government, a government that Watkins has depicted as ill-prepared, and who now sought, essentially, to limit the film's release to cinemas and private screenings by anti-war

groups. It shook confidence in the BBC at a point where the channel was otherwise making groundbreaking programs, and the political interference would see Watkins leave the UK, never to make another film in the country. He

remains a singular, iconoclastic, and generational talent as a director, and his staunch anti-war stance, and continual warnings of nuclear annihilation are some of the best documentaries ever made.

Across this

season, we've considered nuclear war as the bleak punchline of one of the best comedies of the 1960s, the aftermath of a Hiroshima reborn from the ashes, and a nuclear menace made flesh to stalk Tokyo. All of these are

fiction that audiences happily watched, cinematic escapism. The War Game is a warning, and a warning that shook the corridors of power so much that it was denied its proper release.

The film's veracity, its mix of the horrifyingly possible, and the bleakly avoidable, remains striking, remains stunningly effective more than half a century on, and its impact on the very form of the docudrama, the cinematic

consideration of possibilities too frightening for fact, cannot be understated. It is one of the most important films ever made on the threat, and terrible impact, of nuclear war, and a stark

and supremely effective piece of cinema.

Rating: Must See (Personal Recommendation)

The War Game is available to watch online in the UK via Amazon Prime and Apple TV

and on DVD from The BFI.

It is not currently available to stream or buy on DVD in the United States. A full-length BBC Radio 4 documentary on The War Game's release can be found here (UK only)

Next week, and indeed next month, we turn to a British Insititution, in the form of the gore, glee, and of course (Christopher) Lee of Hammer Horror, as The Devil Rides Out.

Support the blog by subscribing to my Patreon from just £1/$1.00

(ish) a month to get reviews up to a week in advance and commission your very own review! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment