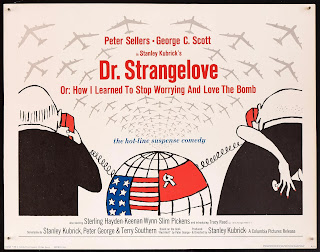

Under the Mushroom Cloud: Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Dir Stanley Kubrick, 1h30m, 1964)

Armageddon can have its funny side. Yes, the world is about to hit by a comet/overrun by zombies/invaded by aliens/raptured to oblivion, but there's comic potential there, in either blackly satirical parables

of American medical care (Gas-s-s-s (1970)), or anti-communist (Sexmission, (1984)), or climate change (Don't Look Up (2021)), or, alternatively use the apocalypse as background for comic japes (A Boy and His Dog (1975), Night of the Comet, (1984) Shaun of the Dead (2004), Zombieland (2009), and This is the End (2013)). Needless to say, most have been made since the fall of communism and the end of the Cold War, largely shy away from

nuclear Armageddon being the punchline of the joke, and if they do, it's long since happened and humanity are picking up the pieces. Most film directors, of course, aren't Stanley Kubrick, and most apocalyptic comedies

aren't Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, the master cinematic craftsman at work on a bleakly satirical tale of nuclear Armageddon caused by madness,

paranoia, and the well-oiled machine of war.

The year is 1962, and Stanley Kubrick is thinking about the end of the world-this is understandable, given it's 1962, and the world has just come as close as it will

do to nuclear war, in the form of the Cuban Missile Crisis. For Kubrick, though, as he continues meticulous research that ran to dozens of books on the subject, this is not a new obsession. He's even considered moving to

Australia, given New York City may end up a Russian target-more immediately, Kubrick has come to the conclusion that the situation is absurd, and that all these military and political writers know nothing. Instead he turns

to Red Alert, a 1958 novel recommended to him by the head of the British International Institute for Strategic Studies, in which a paranoid general launches a nuclear bomb attack on Russia,

and the President and Premier of Russia must co-operate to avoid nuclear annihilation, whilst the general's lieutenant races to uncover the recall code on the base. Kubrick has his next

movie.

Initially intending to make a straight adaption of the film, Kubrick returns back to his initial musings; realising, whilst fleshing out the novel to a screen play, Kubrick, and Red Alert's author Peter George begin to realise that the film's narrative cannot help but play out as a black comedy, the absurd and paradoxical added into the film. Thus, having read his comic novel, The Magic Christian, Kubrick hires Terry Southern, whose brief, one month tenure as the film's co-writer will only further turn the film towards what it eventually

became, an absurd, often blackly funny comedy rife with innuendo, into which Southern had added the faintly sinister figure of Dr Strangelove (Peter Sellers), a composite of Nazi scientists, most notably Werner Von Braun-Kubrick

would promptly name the film after the shadowy nuclear scientist.

Strangelove begins with the Chekov's gun of the bombers, forever in movement, forever no more than two hours

from target being refuelled, accompanied by a string version of "Try a Little Tenderness"-the innuendo, the slow build towards (nuclear) climax has begun, with this strangely romantic foreplay between bomber and

tanker, over which the credits play. We cut to the US, where General Jack D Ripper (Sterling Hayden) sets his apocalyptic plan in action, in the form of "Wing Attack Plan R", allowing a field general to launch a

nuclear attack. The film then cuts to one of these bombers, commanded by veteran western actor Slim Pickens' Major Kong, playing it utterly straight, and close to his typical cowboy heroes, in a film otherwise dotted with

larger-than-life comic performances, as they prepare their bomber for their mission. Until this point, Strangelove's tone has been entirely serious-indeed, Kubrick was concerned that Fail Safe (1962), an entirely straight take on the concept, whose novel largely plagiarised Red Alert would overshadow his own film, so much so that he forced its distributor to delay the film eight months or face legal action.

Meanwhile, as the bombers under Ripper's command

scramble towards Russia, Executive Officer, Mandrake (the first of three roles by Peter Sellers), in full stiff-upper -lip British mode, based on his own RAF experiences, is told to put the base on high alert, locking it down

from the outside world and confiscating all radios. But, as music continues to play from a radio he has impounded, he realises that, far from a first strike by the Russians having decimated America and the West, Ripper has

gone mad. The following scene, in which Ripper's true insanity is revealled, Kubrick shooting Hayden largely from below, phallic cigar lit, is an acting masterclass, as he plots out the trajectory of his plan, forcing

Washington's hand into all out nuclear war, declaiming that "War is too important to be left to the politicians" as he enacts a plan that, in essence, has been designed to remove them from the very beginning.

It is also the point around which the film pivots, from serious dramatic take to bleakly comic. Ripper's plot is, at base, to destroy the world to protect it against the Communist infiltration of Americans'

"precious bodily fluids"-once again, the ribald innuendo raises its head, but here matched to the-very real belief from McCarthy et al-that the Russians were trying to affect Americans via water fluoridation. Ripper's paranoia will only grow throughout the film, as he attempts to deal with the US Army storming the base, and his actions will eventually

doom him and the population of the USA, but for now the film launches into its truly iconic moments in Washington, as the War Room (a colossal and iconic set designed by Ken Adams, and located at Shepperton, due to Sellers'

divorce proceedings), plays host to bleakly comic proceedings.

It is in the War Room, George C Scott's general Buck Turgidson briefs Seller's President Merkin Muffley as to the nature of Wing Attack Plan

R, and the very real threat of nuclear war that may follow. For Sellers, this is undoubtedly his most reserved performance, largely playing the straight man against the increasingly mad cavalcade of generals, military experts,

drunk Russian Premiers, and the belligerent Turgidson himself. For Scott, it's nothing short of masterclass of a performance, though much of it comes from typically Kubrickian trickery, using practice takes where

Scott was less inhibited and reserved, rather than the "real" takes, leading to Scott refusing to work with Kubrick again. It is also here that the utter madness, the absurdity of the situation is laid bare, with

Turgidson suggesting that they use the unexpected attack to launch more bombers, to completely wipe out the Russian counterattack, reasoning with the president that killing twenty million

people by their actions is better than one hundred and fifty million, something that Merkin understandably balks at, despite the slim chances of recalling the bombers.

Into this ever growing powder-keg of a war

room, Kubrick adds in the Russian ambassador, Alexei de Sadeski, another larger than life figure that spends much of the rest of the film spatting with Turgidson, played, with sonorous and looming presence, by Peter Bull,

and who acts, like Turgidson, as a pitch perfect drip-feed of information. Thus, as Merkin stumbles his way through a conversation with the clearly drunk Premier of Russia, de Sadeski slowly reveals that, far from the Russian

targets being unarmed, the Soviets have a terrible-and entirely automated-response, the bleak comedy of Strangelove only heighted by this diabolos ex machina brought into being by the nuclear

arms war as de Sadeski declaims the Russians were scared of a "Doomsday gap". The bleak irony of this machine of doom being dubbed impractical, and its existence to have been announced in just a few days, only further

compounds, as the titular Dr Strangelove finally appears, the seemingly unstoppable build to nuclear climax.

Strangelove is on screen for barely fifteen minutes, but it he, and Sellers, that telegraphs the film's

next change, into open comedy: Mandrake is played utterly straight, Merkin is the straight man in an increasingly dark comedy, but Strangelove is intended to be funny, this peculiar caricature of a German scientist dropped into the USA via Operation Paperclip, and left to his own devices, given a twitchy, uncomfortable sensibility, and a

wandering, seemingly possessed hand that strangles, fights its owner, and Nazi-salutes without warning. Strangelove, thus, is the film's descent into farce. Whilst most of the bombers are recalled, and Mandrake, despite

Ripper shooting himself, and the threat of the Coca Cola Company as he tries to get through to Washington, manages to find the code, and recall the majority of the bombers, (the Russians shooting almost all the rest down),

it is Kong's badly damaged bomber that continues on its mission, down a radio and three engines, to its target.

It is here, having announced the recall of the bombers, and realising that Kong and his crew will

reach the target that Turgidson's wild celebration suddenly halts, his realisation that they are doomed to nuclear war perhaps the single best-and the most shockingly funny-moment and the film's final act begins, with

the bleakly funny and ultimately quixotic attempts to release the bomb, humanity doomed by one last act of heroism, whilst, as doomsday approaches, one last chaotic rush for an advantage begins as Dr Strangelove hypothesises

that humanity could hide from the nuclear fallout in mineshafts, before, as Vera Lyn strikes up, Strangelove rises to his feet, and the bombs fall. It's the one truly profound moment in a film that hurtles, inevitably,

towards the ridiculous and the satirical, with apocalyptic results.

Strangelove, though, is more than just a savagely funny film playing out the fears and predictions of a nuclear

war that never came to be-the film, after all, begins with protestations that the US Armed Forces would never let this come to pass, nor is it simply Kubrick making his one true comedy, and kickstarting a rarefied genre that

the film still remains the best example of. It's more than one of the best scripts of the 1960s, and indeed one of the best casts of the decade, topped by the triple-headed performance by Sellers, and undoubtedly is one

of Kubrick's best, and certainly most commercial films. Dr Strangelove may well be the best film of the Cold War, a perfectly made piece of cinema in which that period's fears are explored, and deconstructed by the satrist’s pen and Kubrick's vision

Rating: Must See (Personal Recommendation)

Dr. Strangelove is available to watch online in the UK via Amazon Prime and Apple TV and on DVD from Sony Pictures.

In the United States, it is available to watch online via Apple TV, and the Criterion Player, and on DVD from Criterion and Sony Pictures.

Next week, we turn to a far starker exploration of nuclear war, against

the background of 1960s Britain, through the lens of the infamous BBC docudrama/psuedo-documentary, The War Game

Support the blog by subscribing to my Patreon from just £1/$1.00

(ish) a month to get reviews up to a week in advance and commission your very own review! https://www.patreon.com/AFootandAHalfPerSecond

Comments

Post a Comment