The Epic: Once Upon A Time In America (Dir Sergio Leone, 3h49m, 1984)

Where did the epic go? By 1984, with the release of Once Upon A Time In America, epics, once the front line in the battle against the attraction of television, were shelved, somewhere. The 1980s arguably only has a handful of epics: Roland Joffé's colossal South American search for faith, The Mission, Richard Attenborough's Gandhi, (in pre-production off and on for nearly twenty years), the ruinous and now critically revisited Heaven's Gate, perhaps the most obvious death-knell of both the Epic and the excesses of the New Hollywood, and Akira Kurosawa's large-scale (and largely French produced) swansong, the magnificent Ran. The epic's lofty pedestal as the ultimate form of cinematic expression had been chipped away by increasingly poor returns on colossaly scaled, and often underwhelming films.

The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) would make back less than a fourth of its budget, whilst 1970's Waterloo would match a cast of thousands (and a £25 million budget) with chaotic cinematography and Rod Steiger mumbling through the titular battle. The epics of the 1970s, with the exception

of the magnificent The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now, both films trying to come to terms with Vietnam, are either epic in their sensibilities,

rather than their budget-look no further than the sweep of Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972), made for a budget of less than half a million dollars, largely verité on the Amazon

River-or are ensemble war movies, like the multinational Tora! Tora! Tora! and the wildly successful Midway.

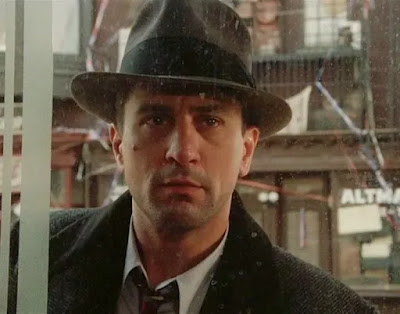

Into this changing world and audience in which the cinematic epic was no longer a surefire way to make money, enters Once Upon A Time In America, the final film by Sergio Leone, a stark, violent, unromaticised version of the gangster lifestyle, in which we voyage back and forth through the memories of David

"Noodles" Aaronson (Robert De Niro), from his childhood, to the 1920s, and beyond.

|

| Robert De Niro as David "Noodles" Aaronson, a figure around which the events of Once Upon A Time In America flow |

The 1960s. Sergio Leone has just made the elagic Once Upon a Time in the West, turning the iconography of thirty plus years of cowboy films on its head and arguably acting as an obituary for the genre. Whilst making West, he's been reading The Hoods, a thinly veiled retelling of its author, Harry Grey's time as a gangster in the 1920s. Intent on directing his next

trilogy, of which West formed the first part, so Leone turned down the chance to direct The Godfather, and thus began a decade or more of cinematic horse-trading.

Leone would approach the project as producer, then director, then producer again, hire and fire Norman Mailer as

writer, before turning to an all-Italian writing team of himself, Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernard, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli, and Franco Ferrini, consider Gerard Depardieu, James Cagney, Richard Dreyfuss and James

Stewart for the cast, whilst Ennio Morricone would have the film's themes written by 1976. De Niro would come aboard in 1981, bringing with him much-needed financial support for the film.

We begin in the 1930s, with three men

on the trail of Noodles; they shoot dead his girlfriend and brutalise the owner of the bar he frequents in systemic and brutal fashion that belies their intent. Noodles, meanwhile is lost in opium, his friends, including Maximilian

"Max" Bercovicz (James Woods), have been slain in a botched heist, and it is here that the film's complex structure begins, not with great fanfare, but the ringing of a telephone.

It takes the film three hours

to circle back round to the nature of that phone call, what it symbolises, and why it weighs so heavily on the gangster's conscience, even doped up as he is, as it rings on and on for nearly three minutes. Noodles escapes

his would-be assassins, flees New York for anonymity in Buffalo, and the film leaps forward into the 1960s, as Noodles is drawn back by a message from a mysterious figure. From here, the film becomes adrift, deliberately

so; here, its gargantuan writing team, two (Benvenuti, and De Bernard) writing the 1920s, Medioli the 1930s, with Arcalli solely writing these Proustian free-associate slips back and forth in time. Much has been

made of the film's structure, what it means; perhaps, the delirium of an ageing man hopelessly lost in his own memories-look no further than the first time it happens, as the film flashes back to the 1920s, and a teenage

Noodles (Scott Tiler) spying on Deborah (Jennifer Connolly, played by an adult by Elizabeth McGovern), who he will have a complex relationship with for the rest of his life.

|

| The childhood sequences of Once Upon A Time in America depict a stunted childhood foreshortened by gangsterdom |

Depict this in chronological

order, as with the disavowed hacked down theatrical cut, and the uncut Soviet release of the film (the latter split into two parts), and you get a middling-to-decent film about a gangster's rise to riches, his downfall,

and his attempts to understand why, all the while having to contend with the mysterious, and corruption-mired Senator Bailey. Tell this story in a linear fashion and it becomes a depiction of a duo of men and their

best friends rising through the ranks of New York's criminal underworld, from young boys to grown men against the backdrop of Prohibition. It also becomes one about stunted youth. We see their diminutive figures, so

often against the colossal bulk of the skeletal Manhattan Bridge, rising out of shot, at once modernity and constant in their lives; the cinematography of Tonino Delli Colli returns, time and again to this all-American

iconography, a landscape haunted by the music of Ennio Morricone.

One of the gang is shot dead in a brutal scene, in which Noodles promptly murders the gunman. Released from prison a decade later, Noodles

and his friends are no different, apart from far more violent, and their childlike impulsive rage, and lost childhoods play out across the rest of the film. There is no glory to these gangsters, none of the glamour and honour, that The Godfather affords the gangster. Noodles and his gang are little more than murderous thugs. Noodles in particular metes out sexual violence against the women who enter his

life, in some of the most unsettling sequences of the film, one of which is against Deborah, much of these scenes being cut out of the bowdlerised 1984 theatrical release.

These are not the principled men

of other works in which the Prohibition is a major plot-point, if not the driving force of the tale, they are not even really men, but men-children, stuck between childhoods cut short and adulthoods that never seem to begin.

De Niro only remains in this perpetual adolescence as the film cuts to him in his 60s, and he begins to uncover exactly what occurred three decades ago, only for him to remain as bemused and childish, reuniting briefly with

Deborah only to completely fail to realise the pain he has inflicted on those around him, and, later, how pain has been inflicted upon himself by others.

|

| De Niro's performance across over fifty years holds together a complex portrait of a man unable to understand his own sins. |

Combined with the cyclical narrative, Leone and his team of scriptwriters, alongside editor Nino Baragli

turn linear narrative into recursive, and only deepen the sense of Leone's gangsters caught in a never ending interplay of events past, present and future; we are dragged forward and backward in Noodles' memories; he

attempts to grasp these fleeting elements of his violent life, as though picking through these scraps, again and again and again, will help him make sense of what he has lost. We return to the Manhattan

Bridge, the recursive pull of memory, of the one moment of childhood happiness, and to the face of Noodles, immutable despite the hours of makeup for the 1960s, and an entirely different actor playing him in the 1920s. Noodles

does not grow, and his story has no true end, no possible direction, but to turn back in on itself.

There is no moment of triumph, there is no great moment of catharsis, only the restless memories of an elderly

man, amongst which Noodles drifts. With its remastering, finally presented in its full remastered cut, this is only felt more strongly.

Once Upon a Time in America is practically the anti-Epic; but it is still an Epic. In its great arc, so Leone confronts the very nature of America, the American Dream, and its hollowness, and

the hollowness of the gangster as American icon as few films have have done since, exploring, and laying bare the violence of the Prohibition Age through Noodles' fragmentary memories.

Rating:

Must See

Once Upon a Time in America is available on DVD and BluRay from Warner Bros. Home Ent and available for streaming

on Disney+

To the modern era of cinema next week, with another Epic redeemed by its Director's Cut, as we consider Ridley Scott's Kingdom of Heaven.

Comments

Post a Comment